Banqueting House at Lacock Abbey

By Stephen Schmidt

Henry Frederick

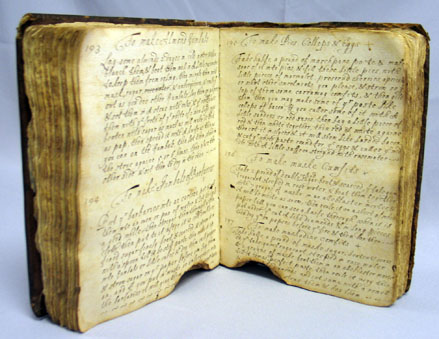

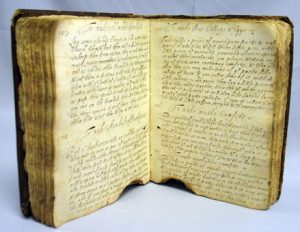

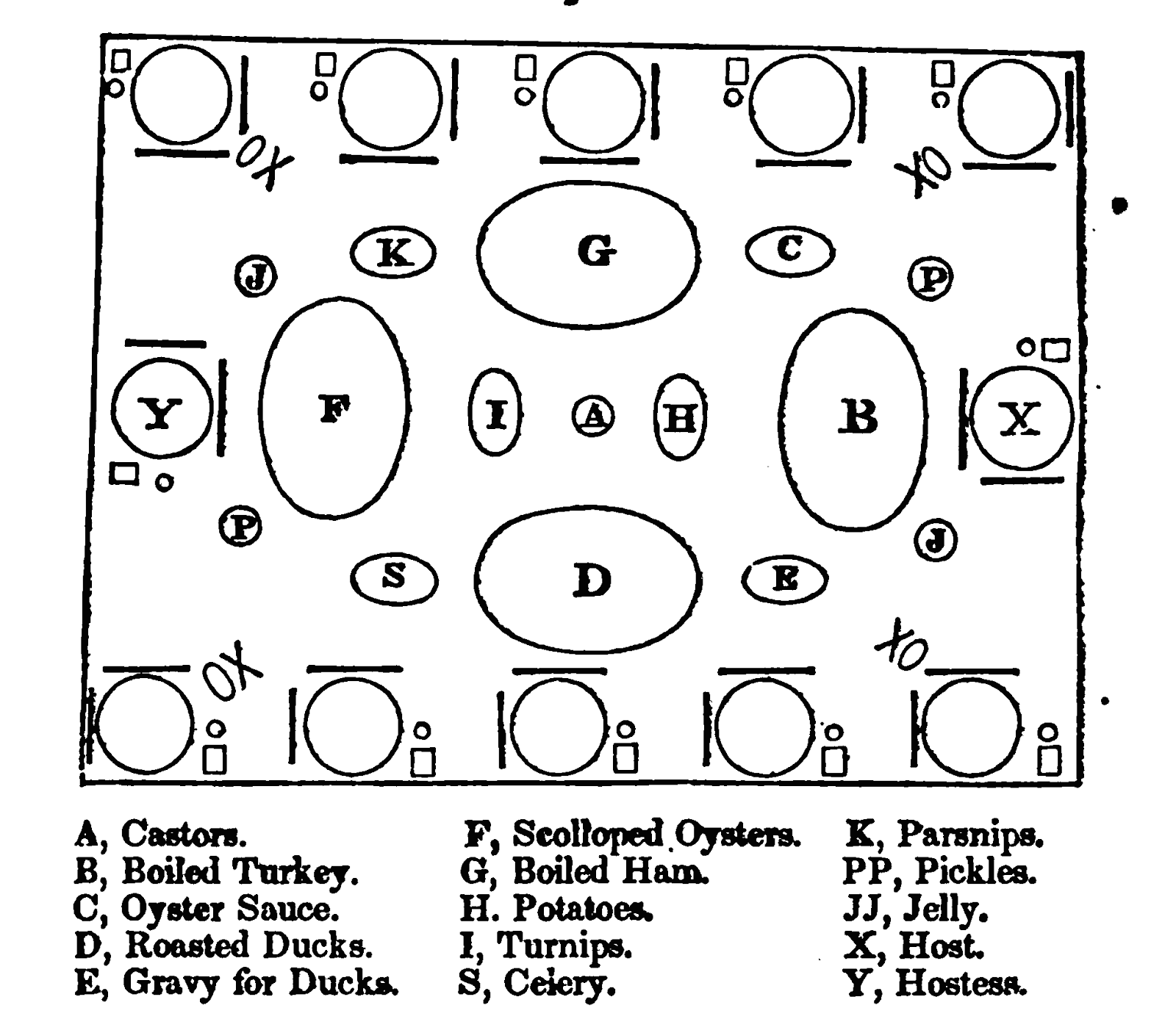

By the time he died in 1612, at only age eighteen, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, had already amassed impressive collections of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and books. His goal as a collector was to show Europe that a strict Calvinist Protestant, such as he was, could also be a proper Renaissance prince, as much a lover of learning and the arts as any Medici duke. Likely also part of this project was a 448-page manuscript recipe book, now held at the Lilly Library, that Henry Frederick commissioned. This book seems odd to us today, in the same way that many Tudor and Stuart recipe manuscripts do. The bulk of the culinary recipes are given over to preserving (preserves, conserves, marmalades, candied fruits, and fruit jellies), and most of the remaining culinary recipes cover sweets of various kinds: candies, sweet syrups (to be diluted with water to make drinks), sweet gelatins, and biscuits and individual cakes. The clue to the book’s seemingly peculiar slant appears at the end of the volume, in a four-page list of “Severall sort of sweet meates fitting for a Banquett.” Henry Frederick’s book is mostly concerned with the conceits of a specialized type of early modern English banquet, one that consisted entirely of sweets. Although banquets were customary following important dinners, they were far more lavish than desserts, as we now think of them. They were more akin to meals of sweets, and they were often staged as stand-alone parties.1

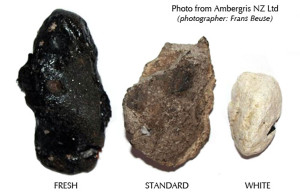

A Closet for Ladies and Gentlewomen, first published in 1608

Banqueting stuff was not ordinary food. Besides being delicious, banqueting stuff was believed to boost wellbeing, facilitating the digestion, quickening the mind, and reviving the libido after a rich meal and enhancing various other bodily functions. In addition, banqueting stuff was extremely expensive due to the costliness of sugar, its prime constituent, and its manufacture was difficult, requiring great knowledge and skill, a refined sensibility, and a deft touch. Thus banqueting stuff radiated an aura of exclusivity. Its recipes were popularly understood to be “secrets” kept under lock and key in the closets, or private sitting rooms, of high-ranking ladies and gentlewomen, who relegated the chores of ordinary cooking to their servants but happily prepared banqueting stuff with their own hands, regarding the task as “a delightful daily exercise”—as John Murrell titled his banqueting book, published in two editions, in 1617 and 1623. It makes perfect sense that Henry Frederick thought to commission a book containing the best and most fashionable banqueting recipes. That he had intimate knowledge of this recherché repertory proved his mettle as a great Renaissance prince and future English king.

The evolution of banqueting

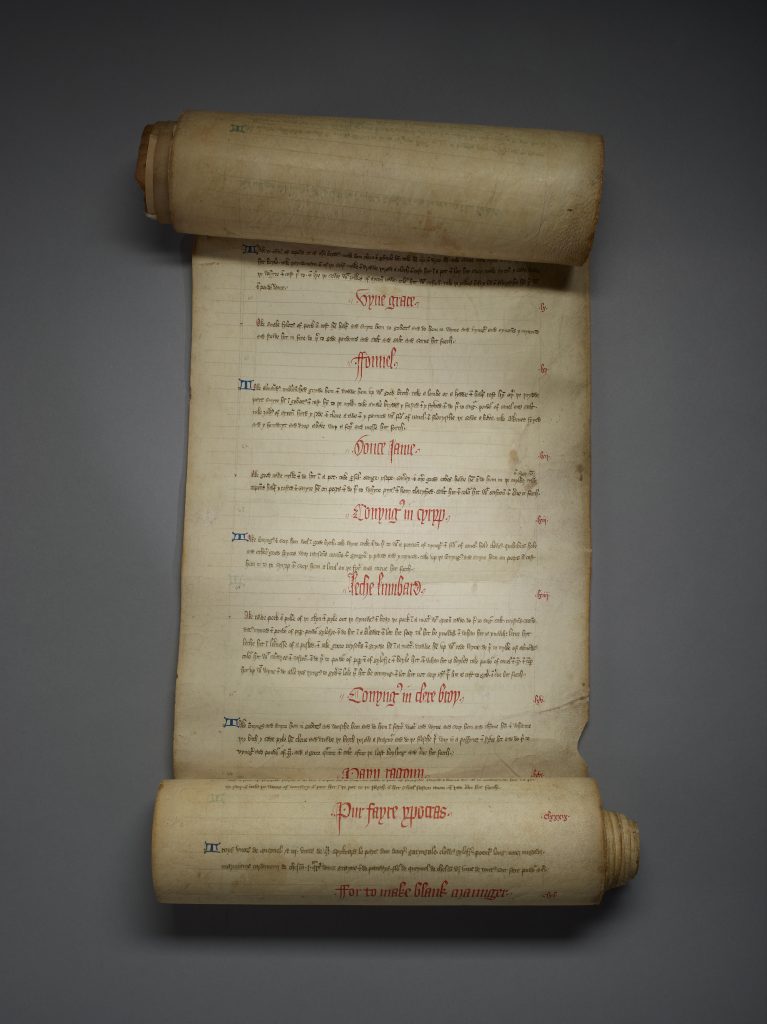

The kernel of banqueting was a post-prandial custom ratified by Thomas Aquinas, the famed theologian, in the mid-thirteenth century: the consumption of “sugared spices”—perhaps similar to the candy-coated fennel and cumin seeds set out at Indian restaurants—after meals in order to promote the digestion. According to humoral theory, which then governed European medicine, the spices were “hot” and “dry,” while the sugar candy that coated them acted catalytically to speed and intensify their warming, drying effects. Thus they cleared the stomach of the cold, damp humors that supposedly filled it after eating, hindering its function, and the stomach, now warmed, could do its job. Sugared spices were medicines—they were prescribed by physicians—but they were also pleasant, which begged the question of whether they could be legitimately consumed during the many fast days of the Christian calendar. Aquinas decreed that they could, for, he wrote, “Though they are nutritious themselves, sugared spices are nonetheless not eaten with the end in mind of nourishment, but rather for ease in digestion; accordingly, they do not break the fast any more than taking of any other medicine.”2

Candied fennel seeds

During the next three centuries, the little service of sugared spices was expanded in different ways throughout Europe to include various other articles consisting of a “warming” substance coated with or cooked with sugar. Perhaps Aquinas might have drawn the line at the more indulgent of these add-ons (like marzipan), but the medieval elite who could afford such things had little difficulty justifying them. After the West assimilated Islamic medicine, in the late twelfth century, sugar became the most pervasive, most broadly efficacious drug in the medieval European pharmacy, and so anything principally constituted of sugar was very nearly a medicine. Strange as it seems to us today, there was then no clear conceptual distinction between confectionery and preserving, on the one hand, and sugared drugs, on the other. Apothecaries sold, and physicians prescribed, sugar, sugared spices, candied lemon rind, and all sorts of other sugared dainties, including, in those lucky places that knew it, marzipan. Fondant, taffy, and even the fanciful sugar statuary bought out between courses at feasts were all considered medicines, their recipes recorded in medical manuscripts, not in cookbooks.

Pewter Spice Plate, early 17th century

In the well-to-do households of medieval England and northern France, the little service of sugared spices evolved into an after-dinner course consisting of the sweet spiced wine called hippocras (after the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates) and sweetened, spiced iron-baked wafers. This little course, eerily suggestive of the Christian communion sacrament, might also include plain and candied spices, but in the greatest households, the spices were served separately, in a different space, in a repast called a voidee (pronounced VOY-dee). The word is from the French voidée, meaning “cleared,” and it referred to the fact that the voidee took place after the great hall, the scene of dinner, had been cleared of people. The voidee was a veritable feast of sugar. It featured additional hippocras, plain spices (presented on ornate gold or silver spice plates in the palaces of royalty and nobility), and all manner of comfits,3 which were passed in a painted wooden coffer called a drageoir: candy-coated spices, seeds, and nuts; candied citrus peel, plant stalks, roots (like ginger), and nuts; and crystallized flower petals and herb leaves. A voidee of sorts might also be served to honored guests in their bedrooms, after the great hall had been cleared for the night. One such fortunate guest was the Burgundian nobleman Lord Gruthuyse, who stayed the night at Windsor Castle following a feasting for King Henry IV, in 1472. The lord and his servant were shown to a resplendently decorated sleeping chamber and a hot bath in an adjoining room. “And when they had ben in theire Baynes as longe as was there plesour, they had grene gynger, diuers cyryppes, comfyttes, and ipocras, and then they wente to bedde.”4

While Lord Gruthhuyse’s bedtime sugar snack was lavish compared to the little nibbles sanctioned by Aquinas, it was certainly no banquet—nor could it have been, for many of the sugary conceits of banqueting had yet to be invented. Medieval cooks to the elite added sugar to all sorts of dishes, including many where we today would not expect to find it, like fish stews or pastas. But medieval cooks used sugar in very small quantities, as a seasoning, typically to intensify the savor of so-called sweet spices such as ginger and cinnamon and to moderate the heat of hot spices such as pepper, cloves, and cubebs. Thus, very few medieval dishes tasted perceptibly sweet and even those that were sweet were by no means “sweet dishes” in modern terms—that is, dishes that tasted primarily of sugar. In the medieval West, sugar was conceptualized as a medicine and a seasoning. Before sweet dishes could emerge, sugar had to be reconceptualized as a thing that was also eaten, a food.

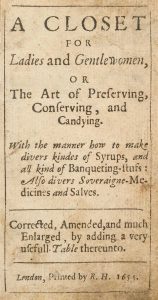

Ludovico Trevisan (1401-1465), Martino’s ruthless and fabulously wealthy employer (by Mantegna, ca. 1469)

This reconceptualization got underway in the fifteenth century, among a circle of elite Italian cooks, particularly the renowned Martino da Como and his acolyte, Bartolomeo Sacchi (known as Platina), who, in 1474, published many of Martino’s recipes in De honesta voluptate et valetudine (“On honorable pleasure and health”), Europe’s first printed cookbook. In many recipes, Martino merely seasoned (or sprinkled) his dishes with ” a little” or “a lot” of sugar, in the medieval manner, but in some recipes, such as those for “white foods” and tarts of pumpkin, almonds, rice, and marzipan, he called for sugar by the half pound or the pound, making these dishes aggressively sweet. Bartolomeo Scappi’s magisterial cookbook of 1570, Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi , took Martino’s new thinking about sugar a giant step forward.5 In addition to seasoning many meat, vegetable, and pasta dishes with as much as half a pound of sugar, Scappi outlined many dishes in which sweetness was the predominant taste: fruit pies and tarts; sweet custards and cream dishes; all sorts of biscotti and cakes; and pastry-like conceits that made use of candied fruits or marzipan. In short, Scappi presented a repertory of sweet dishes.

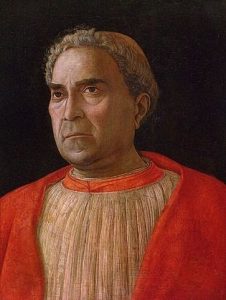

Bartolomeo Scappi (1500-1577)

Interestingly, Scappi placed a number of his recipes for sweet dishes in the final chapter of his cookbook, which covers cooking for invalids and the sick, likely because he believed these dishes were healthful. However, Scappi clearly did not believe that sweet dishes were merely health foods, for he makes liberal use of them in his dozens of luxurious dinner and supper menus. These menus open with platters of candied fruits and then unfold in alternating “kitchen courses” and “sideboard courses,” the former comprising hot dishes such as roasts and meat pies, the latter cold dishes that are more or less equally divided between pungent/salty offerings like salads and smoked or dried fish and sweets such as sugared clotted cream, sweet biscuits and cakes, and marzipan fancies. In a nod to the old ways, the menus conclude with a little service of candied spices, perfumed toothpicks, and, charmingly, small bunches of flowers. Like the ancients, the Renaissance Italians viewed dining as an opportunity for pleasure, so it is unsurprising that sugar, one of the most pleasing foods to the human palate, assumed a more central role in Italian cooking.

Sixteenth-century Europe was primed to fall for Italy’s new ways with sugar, and not only because the Renaissance Italians were then Europe’s tastemakers. Starting in the early fifteenth century, Spain and Portugal had established sugar plantations on four Atlantic island chains stretching from the Iberian Peninsula down to the African Equator. By the last third of the century, the islands had swung into full production, and sugar, historically an expensive and even scarce commodity, had become almost cheap, leading to increased sugar use among the elite and diffusing use downward. During the sixteenth century, the new European demand for sugar caught up with the increased supply, causing prices to edge upward again, but higher prices, instead of tamping down demand, only spurred the Portuguese to produce still more sugar in their new slave-driven sugar ventures in Brazil.

“Still Life with Dainties . . .” Clara Peeters, 1607 (Note Peeters’s “banquet letter”–see footnote 1)

Europe had developed a raging taste for sugar, and a host of new factors—the European discovery of the Americas, the maturation of the shameful slave trade, and the quasi-industrialization of sugar refining in Spanish-controlled Antwerp—had created a market capable of satisfying it. Still-life paintings produced across sixteenth-century Europe tell us that hippocras, wafers, fancy comfits of all sorts, preserved fruits, fruit pastes, Italian biscuits, large and small cakes, and fruit tarts had become customary among the European prosperous. Sugar had been reconceptualized. As a French commentator exclaimed, with a touch of horror, in 1572, “people devour it [sugar] out of gluttony. . . . What used to be a medicine is nowadays a food.”6

The Tudor and Jacobean banquet, 1535-1625

The Tudor and Jacobean English were especially susceptible to the new sugar craze that the Italians had unleashed on Europe, for they were besotted by Italy and keen to imitate Italian fashions. The English nobility and gentry routinely sent their sons to Italy as part of their education—much to the consternation of scolds like Tudor historian William Harrison,7 who viewed Catholic, putatively licentious Italy as “the sink and drain of Hell”—and they boasted of their likeness to the Italians in manner and dress, however far-fetched such claims may have been.8 During the reign of Elizabeth I some three hundred Italian books were published in England, including English translations of Secrets of Alexis of Piedmont (1558), which gave instructions for tableware made from sugar paste, preserves, and sweet wines, and Epulario, Or, the Italian Banquet (1598), a cookbook containing many of Martino’s recipes as rendered by Platina. Elizabeth herself favored the Italian language above all others, even employing an Italian master and bidding foreign dignitaries address her in Italian. Shakespeare set ten of his plays in Italy, which he may have visited.

The Renaissance English imported many sugared elements of the Italian dinner into the English dinner, but it was a specialized sweets-centered Italian meal called a collation that particularly gripped the English imagination. Scappi’s twelve collation menus (one for each month) proceed in three courses, the first consisting of candied or syrup-preserved fruits and nuts, sweet biscuits, and marzipan, the second a mélange of pungent savory foods and sweet dishes (similar to the sideboard courses of dinner), and the third the same but also including fresh fruit and Parmesan cheese. Scappi’s collations are not merely meals. They are early-evening parties that are staged in some pretty spot outdoors during the spring and summer months—Scappi suggests a vineyard or a garden—and include a theatrical performance or other entertainment.

The early English banquet, which emerged around 1535 and ran through the death of James I, in 1625, was proclaimed by its participants and cookbook authors as a repast of sugared medicines–that is, essentially an expanded voidee, and as such traditionally (and safely) English. However, as everyone had to have known, banqueting was actually a voidee reimagined as a Renaissance Italian collation, and critics looking to ferret out insinuations from decadent, depraved Italy had no difficulty finding them, starting with the banqueting houses.

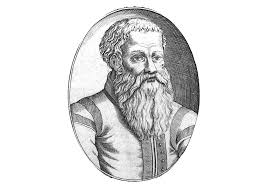

Paul Hentzner (1558-1623)

Theobalds Palace, recreated model–sans banqueting house

Most privileged English had to content themselves with banqueting in their dining parlors. But, when the occasion demanded, the super-privileged could conduct the affair in a specialized banqueting house. These houses variously perched atop towers, or jutted from manor rooftops, or were nestled in a leafy bower on the manor grounds, providing banqueters with the delightful natural views enjoyed by diners at an outdoor Italian collation, without the risk of being rained on in perpetually rainy England. If the views included formal gardens, which they often did, banqueters even saw what the Italians saw, for the gardens were Renaissance Italian imports. Even more Italian than the views were the banqueting houses themselves, including one that Henry Frederick surely knew, at Theobalds, a palace outside London, which Henry Frederick’s father, James I, visited frequently and eventually acquired. When Paul Hentzner, a German tourist, toured the gardens of Theobalds, in 1598, he stumbled upon a “summer house” whose ground floor featured life-size statues of the twelve Roman Caesars set in a semicircle behind a stone table. Crossing by a “little bridge” to an adjoining “room for entertainment,” Hentzner saw “an oval table of red marble,” which can only have been a banqueting table carved in an ornate Italian style.9

Marble table in Lacock counting room

Theobalds was demolished during the Interregnum, but Italianate banqueting houses, or the remnants of them, still survive in several stately houses in the UK, including Lacock Abbey and Longleat, both of which I visited during a recent trip to the UK. Located in the top story of a tower, the Lacock banqueting house is now occupied by bats and can no longer be toured. But the “counting room” on the tower’s second story, once used for the display of precious goods, is open to visitors, and I was told by a docent that its marble pedestal table, carved with classical motifs around the base, is similar in style to the banqueting table in the top story. Befitting their different functions, the two rooms are otherwise quite different. The walls of the counting house are thick and have just a few narrow windows, while the walls of the banqueting house are thinner and filled with windows, enlarging the room and giving it 360-degree views.

Lacock Abbey tower, with banqueting house at top and counting room below

Longleat, astonishingly, boasts seven rooftop banqueting houses, several of which I was privileged to see. They are intimate spaces that could accommodate no more than six or eight seated at a table. The windows have been bricked up, the interiors have been painted over, and all furnishings have been removed, but the Italian influence is nonetheless unmistakable. Four of the houses are domes, a characterizing feature of Renaissance Italian architecture. Looking out over the Longleat rooftop, one can almost imagine seeing the skyline of Venice in miniature.

Longleat rooftop

Longleat banqueting house interior

The bill of fare of the Tudor and Jacobean banquet particularly featured the conceits of the voidee and thereby retained the voidee’s underlying medical justifications. The early banquet always included hippocras and nearly always included wafers, and its most numerous dishes were the nutraceutical conceits of the voidee, namely plain and candied spices and sugared plant materials of all kinds. However, Italian borrowings were numerous, and while most of these had therapeutic value, they strike us today as more geared toward pleasure than cure. Of special importance was the Arabic confection marzipan, a favorite of the Italians since the thirteenth century but unrecorded in England until 1492, where it came to be called marchpane. Any banquet worth its sugar featured a marchpane centerpiece. As typically outlined in period recipes, a marchpane was a thin disc of white-iced marzipan about fourteen inches broad that was decorated with comfits and, on important occasions, surmounted by fanciful sugar statuary. In rarefied precincts, it could be grander still, like the marchpane created by the remarkable food historian Ivan Day, which consists of a marzipan knot garden filled with fruit-preserve “flowers” and a banqueting house in sugar paste. (The footed dishes in the photo are likewise of sugar paste, as is the playing card.) The Tudor and Jacobean English also worked up tinted marchpane as “bacon and eggs” and other cunning knickknacks, and they doted on the new-fangled baked marzipan cakes that the Italians called macaroons.

Jumbles

Another favorite Italianate banqueting cake was jumbles, from the Italian gemello, or twin. As made in the banquet’s first iteration, jumbles were formed by tying ropes of sugary, anise-flecked dough into elaborate knots, making cakes that resembled pretzels (hence the name) but tasted much like soft German springerle (which may well derive from the same Italian source). Also from Italy were the spice-studded (and thus putatively healthful) banqueting bisket breads, whose Latin-derived name denoted that they were baked twice, first to set the dough or batter and then, at a lower temperature, to render the bisket, or biscuit, dry and crisp through and through. The favorites were “prince bisket,” a precursor to today’s lady fingers (and sponge cake), and “white bisket,” essentially hard meringue with anise seeds. Less favored was the rock-hard “bisket bread stiff,” which was essentially the same as today’s classic Italian anise biscotti and which was surely consumed the same way, first dipped in sweet wine to soften. The Italian banqueting conceits popularly known as kissing comfits are familiar today from the line in Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor: “Let the sky rain potatoes . . . hail kissing comfits and snow eringoes . . . .” Kissing comfits were little slips of hard sugar paste imbued with musk, a glandular secretion of an Asiatic deer believed to be an aphrodisiac. The preserved sweet potatoes and eryngo roots (sea holly) referenced in the line were believed to have the same warming effects on the nether regions. One suspects that Aquinas would not have approved.

Sugared fruit preserves were not specifically Italian but they were starring attractions of the Italian collation, so they inevitably became star attractions of the early English banquet too.10

Quince paste (membrillo)

The fruit most commonly preserved throughout early Europe, including England, was quince, in part because quince was believed to have many health benefits, and in part because its high pectin content made possible all manner of jellied conceits. Whole quince and quince pieces preserved in thick syrups appeared on early English banquet tables in myriad hues, from gold, to rosy pink, to ruby red, depending on how the fruit was cooked. Even more fashionable was the quince preserve called marmalade, which the English initially imported from Portugal, where it was invented (and hence its name, from the Portuguese marmelo, or quince), but which the English soon learned to make themselves. Like modern quince paste, often called by its Spanish name membrillo, quince marmalade was a smooth, stiff confection that could be picked up with the fingers, not a nubby bread spread. It was sometimes put up in matchwood boxes, to be served in cut pieces, sometimes “printed” in fanciful individual molds, and sometimes squirted in pretzel-like knots. Quince jelly, or quiddany (from the French cotignac), too, was a stiff confection and was often printed. There were also quince “pastes,” quince “cakes,” quince “chips,” and still other types of quince preserves, whose methods are mostly opaque to me. By the seventeenth century, all of these conceits had come to be made with innumerable other fruits, including oranges, which were worked up into a marmalade that had the same smooth solidity as its quince forebear. So fond were the English of these sugared fruit delicacies that they devised a specialized implement to consume them: the sucket fork (from succade, candied citrus peel). It had fork tines at one end and a spoon bowl at the other, facilitating both the spearing of solid preserves and the scooping of wet preserves and their ambrosial syrups.

Pewter Sucket Fork, London, ca. 1690

Rounding out the fare of the early banquet were several sweets that had long been part of elite English fare. These included the highly esteemed sweetened animal gelatins, called jellies, which typically consisted of a clarified calves’-foot stock flavored with spices and wines and/or citrus juice. Calves-foot jellies were sometimes colored and, in palaces, they were fancifully molded and turned out, but most banqueters encountered them as described in a banqueting cookbook of 1608, “cut . . . into lumps with a spoone.” There was also a specialized jelly called leach (from a French word meaning slice), which was creamy and rose-water-scented and was set with the new-fangled isinglass, made from sturgeon swim bladders. A favorite banqueting stuff “used at the Court and in all Gentlemen’s houses at festival times,” as Hugh Plat wrote in Delights for Ladies, his banqueting cookbook of 1609, was gingerbread. The common sort, called colored gingerbread (because it was typically tinted rusty-red with ground sandalwood), was made by boiling bread crumbs, wine or ale, sugar and/or honey, and an enormous quantity of diverse spices into a thick paste, which was then printed in elaborate molds and dried to a chalky-chewy consistency. Colored gingerbread originated as a medicine, and it tastes like one: its spicing is almost caustic. In the late seventeenth century, as the banquet petered out, colored gingerbread waned, its name assumed by early forms of today’s baked molasses gingerbread, which came to England from the Netherlands or France.

“Making of cheese,” from a 14th century copy of “Tacuinum Sanitatis,” an Islamic health handbook translated in Sicily. The book glosses fresh cheese as “moist and warm.”

In The English Hus-Wife (1615), Gervase Markham’ closes his banquet menu with fruit, both fresh and cooked, and cheese, either aged (like Parmesan, a favorite Italian import) or fresh cheese (think ricotta, though true ricotta is made differently), which English banqueters liked cloaked with thick cream and sprinkled with coarse sugar. If the banquet were simply a glorified voidee, fruit and cheese would never have found a place in it, for no medical authority, I believe, would have claimed that these foods served to open up, fire up, and clean out the stomach, as the voidee was supposed to do.11 Fruit and cheese belied the banquet’s spiritual proximity to the Italian collation, a meal geared more to pleasure than to cure.

The later Stuart banquet, 1625-1700

In 1600 England imported only about one pound of sugar per capita annually, and most English people consumed far less sugar than that, if any at all.12 Sugar was very expensive, and only the wealthy could afford to use it. And so they did, liberally, especially when they banqueted, and not only because they believed that sugar was healthful and because they really liked it, but also because they delighted in the conspicuous consumption of a substance denied to most. The snob value of sugar began to falter in the 1630s, when the new English sugar colony of Barbados, dependent, as all European sugar colonies were, on the brutal exploitation of enslaved Africans, began to swing into production. By the time of Charles II’s ascension to the throne, in 1660, the price of English sugar had fallen to a small fraction of what it had been in 1600. As prices fell English sugar consumption rose in tandem and, critically, much of the increased consumption occurred within the middling classes. Thus Hannah Woolley, who styled herself as cookbook author and behavior advisor to the rising professional and merchant classes, provided a range of banqueting plans, from deluxe to cheap, in The Queen-like Closet (1672). “I am blamed by many for divulging these Secrets,” she wrote, referring to the highly privileged, who wished to keep banqueting secrets to themselves, “and again commended by others for my Love and Charity in so doing; but however I am better satisfied with imparting them, than to let them die with me. . . . ”

Once the hoi polloi were able to scrounge enough sugar to banquet, the elite who set banquet fashions began to lose their appetite for unremitting sugar meals. By the last third of the seventeenth century, the syrupy hippocras was often replaced by lighter fruit and flower wines, and the sugared medicinal tidbits that once covered banquet tables were relegated to a side dish or two. Marchpane, if served at all, came to the table as little knickknacks bought from a comfit-maker; the ancient spice bomb called gingerbread dwindled toward extinction. Hostesses retained their affection for fruit preserves, gelatin jellies, and biskets, but these “ate” differently now, for they were paired with sweet dairy dishes called “creams” and “butters” and with buttery little cakes that we today would call cookies.13

“. . . Dance Around the May Pole,” Bruegel

England had long been a dairying culture, and milk, butter, and cheese had long been staple English foods. This being the case, it seems unsurprising that dairy foods gained favor at banquets, for all long-enduring foreign fashions eventually begin to naturalize in conformance with native tastes. Tudor and Stuart literature contains many references to dairy foods as the stalwart fare of country folk. In his 1542 health manual, Andrew Boorde describes cream eaten with berries as a “rural man’s ‘banquet’” (although he decries the combination on health grounds, claiming that “such banquets have put men in jeopardy of their lives.”) Fresh fruits, cream, and local iterations of butter-rich cakes were typical treats of outdoor country festivals like May Day, which Robert Herrick frames as an idyll of “Cakes and Creame” in his famed poem “Corinna’s Gone a Maying.”

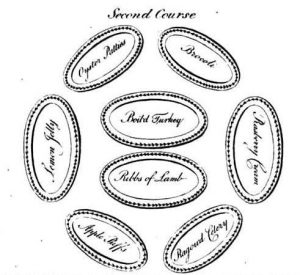

Illustrated second course showing barley cream at right (18th century)

The elite, meanwhile, enjoyed sophisticated dishes called creams in the lighter, sweeter, generally more delicate second course of dinner, which intermixed savory morsels like roasted songbirds, sauced lobster meat, and prime seasonal vegetables with creams and other sweets like gelatin jellies and fruit tarts. Some diners partook only of the savory dishes or only the sweet, while others first nibbled on a bit of lobster and peas and then filled a fresh plate (begged from a waiter) with a fruit tart and lemon cream. Since the elite English were already accustomed to eating creams at dinner, the inclusion of creams in banqueting was logical. Hostesses just had to make sure that the creams served in the banquet were “contrary from those at dinner,” as Hannah Woolley advises her readers in The Queen-Like Closet.

Shrewsbury Cakes, which were marked with a comb (courtesy Susana Lourenco)

Buttery little cakes had begun to steal onto the banqueting scene even before the cachet of sugar had waned. In The English Hus-Wife, Gervase Markham outlined both the then-conventional sugary anise jumbles cribbed from Italy and “finer jumbals,” which he extoled as “more fine and curious than the former, and neerer to the taste of the Macaroone.” The groundbreaking feature of these “finer” jumbles was not the pounded almonds but the “halfe a dish of sweet butter” (six ounces, probably) they contained, along with “a little cream.” In modern terms, Markham’s almond jumbles were rich, crumbly butter cookies. John Murrell finds room for almond jumbles in several otherwise sugary banquet bills of fare set forth in the 1623 edition of A Delightful Daily Exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen. Murrell also includes two other cakes of similarly buttery composition, Counties Cakes and Shrewsbury Cakes, both of which were regional specialties. By the mid-seventeenth century, butter-laden jumbles—typically sans almonds—had almost completely routed their sugary, anise-flecked Italian predecessors at banquets, and Shrewsbury cakes had become banquet staples. The name “counties cakes” disappeared, but “sugar cakes” “fine cakes” and simply “cakes,” likewise banquet standbys, were much the same thing. In the late seventeenth century, the banquet incorporated a startling novelty: the currant-studded Portugal cakes, likely named for the Portuguese queen consort of Charles II, Catherine of Braganza. While Portugal cakes were compositionally similar to the other buttery cakes, their slightly more liquid batter was beaten with the hand until light and fluffy and then baked in individual fancy tins, making, essentially, little currant pound cakes. Modern Anglo-American baking, with its buttery cookies (or, in England, biscuits) and buttery cakes, was emerging.

Christian IV of Denmark (1577-1648)

When, exactly, the creams and their firmer, spreadable cousins, the butters, joined banqueting stuff is a vexing question. No sign of this momentous occurrence can be gleaned from English cookbooks, either printed or manuscript, prior to the Restoration, in 1660. But other evidence suggests an earlier incursion. What, for example, was Shakespeare intending to convey in that curious line in Romeo and Juliet: “We have a trifling, foolish banquet toward”? Context makes clear that the impending banquet is a sweets banquet. But do the words “trifling” and “foolish” merely mean silly, frivolous, idle—common period associations with banqueting—or are they also a play on the various creams called trifles and fools, which at some point indeed became banqueting stuffs? The latter seems possible if John Harington’s hilarious account of a 1606 banquet masque at Theobalds is authentic. Staged in honor of James I and his brother-in-law, King Christian of Denmark, the masque was played by persons whose “inner chambers” were flooded with wine, one of whom tripped and deposited “caskets” filled with “wine, cream, jelly, beverage, cakes, spices, and other good matters” in King Christian’s lap, so soiling his garments that they “defiled” the bed to which the discombobulated sovereign repaired for a lie-down. Alas, we cannot place overly much faith in this cream-soaked story, for it is mentioned by no other Jacobean commentator.14 Henry Frederick’s recipe book is less than ideally helpful on this question. Its recipes for creams appear in a section headed “Cookery,” which contains both dishes served during the principal courses of the meal and banqueting stuffs.

Early-modern English creams divide into two distinct chronological groups: those that emerged prior to 1600 (some, indeed, centuries earlier), and those that became current after 1650. Clotted, whipped, churned, and rennet-clabbered creams all belong in the pre-1600 group. The means by which these creams were given substance were simple, but the creams were not simple in look. The whipped cream called “snow cream” (an international favorite, also outlined by Scappi) was often draped over a rosemary branch stuck into a (cream-shrouded) bread loaf, and clotted cream, at some point in the seventeenth century, came to be sliced, overlapped on an inverted bowl, and sprinkled with sugar and rose water, making the charmingly named “cabbage cream.” Also predating 1600 were various cream custards, some smooth and some intentionally curdled, which often went by the name “cast cream,” as well as the so-called “Norfolk fool,” which consisted of smooth cream custard poured over sack-soaked bread toasts. This dish, no doubt, was a precursor of the later trifle, but, until around 1690, “trifle” designated cream clabbered with rennet. Finally, the early creams included a clutch of medieval dishes that the seventeenth-century English were beginning to refer to as fools. These were made by combining cream with cooked fruit pulp, with or without a thickening of eggs. Apple and quince creams were on the scene before 1600, and possibly gooseberry cream was too. Later, plum cream, apricot cream, and still others emerged.

Syllabubs by Ivan Day

The post-1650 creams included “sack cream,” “raspberry cream,” “orange cream,” and “lemon cream,” which were often made simply by clabbering raw cream with sack, pureed raspberries, or the juice of Seville oranges or lemons (all of which are acidic), but which sometimes involved cooking with eggs. Also part of the later group were the caramel-crusted cream custard called “burnt cream” (that is, crème brûlée), creams made by boiling cream with pounded almonds (“almond cream”), chocolate-flavored creams, and creams consisting of cream cooked with starch (“barley cream” and “rice cream”), some of which were made stiff enough to mold and turn out. A particularly fashionable cluster of late creams were actually jellies (and sometimes referred to as such) consisting of cream set firm with a bone stock or isinglass. These were sometimes served in slices, like the old leach (which was a precursor), sometimes molded in a V-shaped beer glass and turned out, making “piramedis cream” (that is, pyramidal), and sometimes molded in other forms and referred to as “blancmange” (which most Americans today know as panna cotta). Derived from an earlier libation of the same name, the creams called “syllabub” were various and sundry permutations of whipped and/or clabbered cream afloat on wine, cider, or citrus juice. Finally, there was the daring new cream of royalty and nobility that made its first appearance in England during the reign of Charles II. This was “ice cream,” which, as then made, was simply cream that was sweetened with a little sugar, flavored with orange flower water, and still-frozen in a deep pan before being turned out.

Francois Pierre de la Varenne (1615-1678)

There is a reason that the banquet was flooded with new creams after 1650 and became, essentially, a repast of fruits and creams eaten with biscuits and buttery cakes. In the mid-seventeenth century, the French became Europe’s new culinary tastemakers, displacing the Italians. French recipes and French culinary ideas invaded elite English cooking, inaugurating an English vogue for French cuisine that would endure for the next three centuries—along with a corresponding nationalistic culinary backlash. England received much of its first news of the new French cooking through three cookbooks associated with the revolutionary French chef François Pierre de la Varenne: Le Cuisinier François (1651), of which La Varenne is indisputably the author, and two later works often attributed to La Varenne but likely written by others, Le Pastissier François (1653) and Le Confiturier François (1660). Cuisinier and Pastissier were both promptly translated into English, and the former became a runaway bestseller. Confiturier was not translated into English, but many educated English people of the day knew enough French to read it and no doubt did. The book revealed the secrets of the dazzling French collation, a derivative of the Renaissance Italian collation and thus a cousin of the English banquet. In addition to recipes for preserves, biscuits, macaroons, marzipan, and sweet beverages, which had long been the stuff of banqueting, the book included a chapter titled “Butters, Creams, and Dairy Stuff.” If the French featured dairy stuff at their collations, any bang-up-to-date English banquet hostess was sure to follow suit. Beyond simply ratifying a fashion for dairy stuff at banquets, the French contributed many specific dishes and ideas. The new butters seem to have been mostly French, although inspired by the medieval pan-European almond butter. Burnt cream and almond cream, too, are likely French (although some English people will argue about the former), and the white jellies and ice cream likely came to England under French auspices, although they are not French inventions. The molding and turning out of creams and jellies, which transformed the look of the banquet table, was popularized by the French, who molded and turned out all sorts of things. And beyond the dairy stuff, there were new French biscuits, forerunners of the eighteenth-century French biscuit craze that led the English to spell the word the French way while continuing to pronounce it as they always had. And let’s not forget lemonade, which La Varenne introduced to Anglo-America as a seventeenth-century French collation beverage.

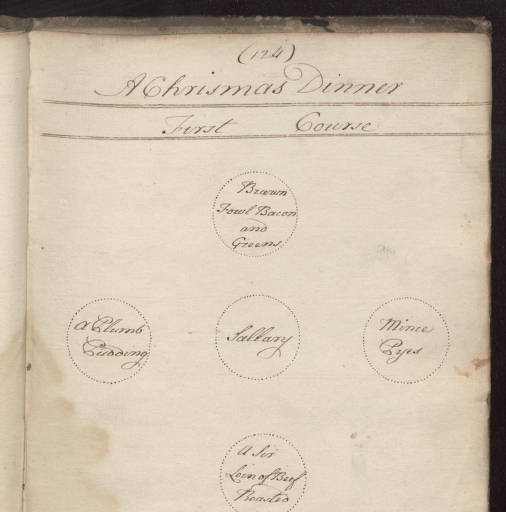

Shortly before the turn of the eighteenth century yet another new-fangled French culinary idea, dessert, pervaded England. The word “dessert” fairly quickly routed the old word “banquet,” but not because early desserts were all that different from banquets in content. What had changed was the broader conception of sweet dishes. Through most of the seventeenth century, sweet dishes were considered special, so much so that even the elite often dispensed with a banqueting course at dinner on ordinary occasions. But as sugar became ever more affordable and familiar, the wealthier classes came to expect that any dinner should be “de-served” with a course of sweets. Which sweet dishes belonged to dessert and which were proper to the complicated second course remained wildly unsettled matters in England for next 150 years, but Americans had sorted things out by the end of the eighteenth century. As Louise Conway Belden points out,15 the mixed savory and sweet second course was problematic in America because it required servant waiters to change (and wash) extra plates, and American servants were perennially in short supply. So American hostesses made the second course entirely sweet (it was trending in that direction anyway by this point), and they added, on formal occasions, a little caboose course of fruits (fresh, preserved, and dried), nuts, candies, and liqueurs. Although the distinction was often lost, properly speaking, the little extra course was the actual “dessert,” while the second course was “pastry” or “pastry and pudding,” its primary constituents.

When the upper classes adopted the dinner service called “à la russe” in the late nineteenth century, the French iteration of the little extra dessert course arrived in America. It differed in many details from the earlier American version, but its principal conceits were the same: fresh and dried fruits, candied fruits and citrus peels, nuts, dragées and other confectionery, and liqueurs. At formal wedding dinners and holiday dinners a similar little dessert extra course is still brought forth today, bearing more than a little resemblance to the original Anglo-American sweets banquet.

- The modern English word “banquet” is a French word derived from the Italian banchetto, or “little bench.” According to OED, cognates of the modern word entered English with three different meanings: a feast (first use 1483); a between-meals snack (first use 1509); and a repast of sweetmeats (first use 1523). These three meanings likely reflect the early use of banchetto in Italian, which, disappointingly, OED states “has not been investigated.” In most of Renaissance Europe cognates of “banquet” designated a feast, except in Holland, where “banquet” also referred to sweets banquets quite like those in England and where, even today, people are given their initials in chocolate, called “banquet letters,” on their birthdays. ↩

- Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Viking, 1985), 99-101. ↩

- In medieval England, a comfit was any spice, seed, nut, flower, leaf, or other small plant material preserved in any manner with sugar. By the seventeenth century, the meaning of “comfit” had narrowed, so that the word denoted only articles encased in a hard shell of sugar candy, like today’s Jordan almonds. ↩

- William Brenchley Rye, England as Seen by Foreigners in the Days of Elizabeth and James the First (London: John Russell Smith, 1865), xli-xliii, file:///C:/Users/user/Documents/Research/England%20as%20seen%20by%20foreigners,%20all.pdf ↩

- Terrence Scully, The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570), a translation of Scappi’s original work with extensive commentary (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011).

↩

↩ - Jonathan Hersh and Hans-Joachim Voth, Sweet Diversity: Colonial Goods and the Welfare Gains from Trade after 1492, 9 file:///C:/Users/user/Documents/Research/Sweet%20Diversity.pdf ↩

- William Harrison, The Description of England, ed. Georges Edelen (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2011). ↩

- Rye, England as Seen by Foreigners, xlix. ↩

- Paul Hentzner, Travels in England During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, 38 file:///C:/Users/user/Documents/Research/England%20as%20seen%20by%20foreigners,%20Hentzner.pdf ↩

- Fruit preserving came to New England early on. The English traveler John Josselyn reported of the women of New England, circa 1663, “Marmalade and preserved damsons is to be met with in every house….The women are pitifully toothshaken, whether through the coldness of the climate or by the sweetmeats of which they have store, I am not able to affirm.” Indeed, the banquet clearly came to New England too, in some form or fashion, for Edward Winslow, a passenger on the Mayflower who served several terms as governor of Plymouth Plantation and acted as the colony’s de facto ambassador to England, brought a set of banqueting trenchers from England to Massachusetts, probably in the 1630s. See Louise Conway Belden, The Festive Tradition: Table Decoration and Desserts in America, 1650-1900 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 95, 126. The two passages quoted by Belden occur in Josselyn’s Account of Two Voyages to New England Made in the Years 1638, 1663, first published in 1672. See pages 146 and 142 of the 1865 Houghton edition: https://books.google.com/books/about/An_Account_of_Two_Voyages_to_New_England.html?id=eIlDAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false ↩

- The little I know about humoral food beliefs mostly comes from Tacuinum Sanitatus, an Arabic health handbook translated into Latin, in Sicily, in the thirteenth century and highly popular in medieval Europe. The following edition, which I bought for a pittance online, has gorgeous color reproductions of original medieval illuminations: Luisa Cogliarti Arano, The Medieval Health Handbook, translated and adapted by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook (New York: George Braziller, 1976). ↩

- C. Anne Wilson, ed., Banquetting Stuffe (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991). ↩

- Some later Stuart banquets also included tarts filled with fresh cheese, called cheesecakes, and fruit tarts, but my impression is that both were more commonly served in the second principal course of the meal. ↩

- James Shapiro argues against the authenticity of this account in The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 (2015). To read the entire story, see Norman Egbert McClure, ed., The Letters and Epigrams of Sir John Harington (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930), Letters 119 https://archive.org/stream/lettersepigramso00hari/lettersepigramso00hari_djvu.txt ↩

- Belden, The Festive Tradition, 190-1. ↩

![Mary Randolph[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Mary-Randolph1.jpg)

![grea001[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/grea0011-214x300.gif)

![9780226430362[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/97802264303621-199x300.jpg)