On Saturday, September 20, 2008, the excitement was beginning to grow on Breaker Bay, near Wellington, New Zealand . . . [A] crowd had gathered to investigate a strange object that had washed up ashore during the night. It was large, perhaps the size of a 44-gallon drum . . . No one had seen it arrive. It was just there on the sand . . . roughly cylindrical in shape . . . the color of dirty week-old snow.

As the news media arrived and locals began breaking off pieces of the mass with garden tools, Christopher Kemp, an American biologist on an academic visit to New Zealand, watched the scene with growing amazement. Was it an aspect of New Zealand national character that made people act this way?

Then a rumor began to circulate. The mysterious object was ambergris.

![9780226430362[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/97802264303621-199x300.jpg) Kemp had never heard of ambergris, and the spectacle on Breaker Bay prompted him to embark on an obsessive study of the substance during his two-year stay in New Zealand. He phoned, emailed, and flew across continents to pry whatever intel he could (often frustratingly little) from the shadowy global network of professional ambergris hunters and traders. He sniffed the stuff in museums and absorbed the wisdom of experts. And he combed remote New Zealand beaches, often by himself and sometimes for days at a time, in hope of finding treasure of his own, which, sadly, he never did. When he returned to the United States, Kemp wrote a brief book about ambergris titled Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris (The University of Chicago Press, 2012), which tells us what ambergris is, gives us a sense of its historical and current uses, and recounts, in lushly descriptive and often lyrical prose, the author’s dogged beach treks in search of it. For those curious about ambergris, a perfume ingredient that was once also used in food, the book is a marvelous find.

Kemp had never heard of ambergris, and the spectacle on Breaker Bay prompted him to embark on an obsessive study of the substance during his two-year stay in New Zealand. He phoned, emailed, and flew across continents to pry whatever intel he could (often frustratingly little) from the shadowy global network of professional ambergris hunters and traders. He sniffed the stuff in museums and absorbed the wisdom of experts. And he combed remote New Zealand beaches, often by himself and sometimes for days at a time, in hope of finding treasure of his own, which, sadly, he never did. When he returned to the United States, Kemp wrote a brief book about ambergris titled Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris (The University of Chicago Press, 2012), which tells us what ambergris is, gives us a sense of its historical and current uses, and recounts, in lushly descriptive and often lyrical prose, the author’s dogged beach treks in search of it. For those curious about ambergris, a perfume ingredient that was once also used in food, the book is a marvelous find.

The original English word for the substance was simply “amber,” derived from the Arab anbar via the French ambre. When, at a later point, ambre/amber came also to designate fossilized resin, fragrant amber came to be distinguished as ambre gris, or gray amber, and hence the modern English word (whose last syllable is generally pronounced griss or greez). Sperm whales are the producers of the substance. The whales subsist on enormous quantities of squid, and an occasional unlucky animal (perhaps one in one hundred) gets squid beaks caught in its gut. As the mass grows, the animal secretes a fluid around it, transforming it into ambergris, much as some oysters turn sand grains into pearls, although in the case of whales, unfortunately, it appears that the mass eventually proves fatal. Ambergris can be harvested directly from its source—by the early nineteenth century, whalers knew that lean, sickly, torpid animals often bore the commodity—but, historically, it was far more commonly a thing that washed up on the shore, its origins mysterious. As Paul Freedman explains in Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination, some (including Marco Polo) knew that ambergris came from whales as early as the thirteenth century. However, this connection was only “dimly and inconsistently” understood by the world at large until two Massachusetts savants, in the 1720s, published separate papers conclusively proving the link, their expertise almost surely gathered by way of the Nantucket whaling industry.

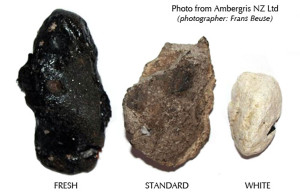

Throughout its history, which reaches back to antiquity, ambergris has been used primarily in perfumes, in which it both functions as a powerful fixative, causing perfumes to linger far longer on persons, fabrics, gloves, or sachets than they otherwise would, and also contributes a fragrance of its own. Everyone who has smelled ambergris (unfortunately, I am not among the number) agrees that the fragrance is compelling, but no two people describe the fragrance in the same terms. Perfumers classify the aroma as “animalic,” which could perhaps encompass the scents that Kemp detected in a particular piece, which included cow dung, tobacco, rotting wood, drying seaweed, and open grassy spaces on a beach. But there are sweeter, lighter notes too, such as violets and vanilla. One of the reasons the fragrance is so difficult to pin down is that ambergris smells different depending on whether it has been expelled from the whale only recently (or indeed excavated from a whale carcass) or has been bobbing about on the surface of the world’s oceans for decades. When fresh it is distinctly fecal, as one would expect. When it has aged (and its key chemical component, ambrein, has oxidized into slightly different compounds), its aroma becomes complex—and magical. Its color and texture, too, change as it matures, from dark and putty-like to whitish-gray and barely malleable, like sealing wax.

Partly because ambergris is so mutable, beached blobs of sewer grease and other garbage are often mistaken for the real thing—as proved, alas, to be the case of the mass that came ashore on Breaker Bay in 2008 and caused so much excitement. The sovereign test is to probe with a hot needle: if the specimen is indeed ambergris, it will “melt into a thick, oily fluid the color of dark chocolate,” writes Kemp, and release an ineffable aroma. And you will be suddenly richer. The highest-quality white ambergris sells for $8,000 or more per pound in Europe, where it is in demand by many of the big perfume houses (although they are cagey about using it, likely because its possession and trade are illegal in many places, including the U. S. and Australia). This is not quite the present value of 24-karat gold but surprisingly close.

Ambergris was never nearly as common in cooking as in perfume-making, but its use in food was very early. I do not recall seeing it in Apicius, and I would be surprised to it find there, as it strikes me as out of sync with the usual Apicius flavor notes. But ambergris did play a part in medieval Arab and Indian cuisines, which adapted it from the court cuisine of early-medieval Persia, along with various other fragrances that modern Westerners do not expect to find in food: musk and civet (both animal-derived); roses, orange blossoms, and other flowers; aloe and sandal woods; and camphor. There is, for example, this recipe from the fifteenth-century The Ni’matnama Manuscript of the Sultans of Mandu (Routledge, 2012):

Boil the meat well, take it off [the fire], dry it, and fasten it to a wooden skewer. Mix saffron, white ambergris and rosewater together and rub it on the meat. Put it in a cooking pot and add rice. Put in fresh ginger, onions and salt and cook it. Serve it with good gravy.

Since ambergris was part of medieval Arab cuisine, it might well have entered the cuisines of the medieval European privileged, which incorporated many Arab influences. (How many is a matter of disagreement; my personal sense is rather a lot.) But I do not recall having seen it in any English or French medieval recipe manuscript. I would be curious to know if it appears in medieval Italian recipe manuscripts (which I have not studied), for Renaissance Italian court cooks used it in biscotti and other sweets, typically in combination with musk. By the seventeenth century, the French, too, had adopted it. In La Varenne’s Traité de Confitures (1650) ambergris—almost always paired with musk—scents diverse candied-fruit conceits, sugar-paste pastilles, pralines, marzipans, wines, and lemonade, as well as a preparation called “crème, autre façon,” which is basically our crème anglaise. La Varenne gives these directions for preparing both musk and ambergris for use in recipes (my translation). There were other ways, but this was a particularly common one.

To prepare your musk in the proper way, put it in a little cast-iron mortar, pound it with a pestle of the same material, mix it with a little powdered sugar, and after everything is well ground, put it in a paper so that you can make use of it as needed. You can prepare ambergris in the same way and even mix them together, to use as much for beverages as for preserves.

In due course, ambergris infiltrated English cooking by way of the Italians and the French, whose cuisines were much admired and emulated in early-modern England. Kemp cites a “curious lady” of the eighteenth century, who claimed to have read, in obscure sixteenth-century sources, that ambergris was “the haut-gout” of Tudor court circles starting in the early 1500s. Perhaps this was true (if so, the fashion would have been imitated from the Italians), but there is very little mention of ambergris in sixteenth-century English printed and manuscript cookbooks—and indeed there remains little until the time of the Restoration, in 1660, when cookbooks are suddenly redolent of the stuff. Robert May, in The Accomplisht Cook (1660, 1665), has some twenty recipes. Hannah Woolley, in Queen-like Closet (1672), has close to thirty. Woolley’s fondness for the material is interesting, for she addressed the upper-middling classes as much as she did the very wealthy. Perhaps ambergris was not quite as rare and expensive in seventeenth-century England as we might suppose.

Both May and Woolley outline ambergris-infused medicinal drinks (some of which were pleasant and were more enjoyed than “taken”) and both have hartshorn jellies (gelatins) flavored with the substance. But otherwise their recipes differ. Woolley focuses on ambergris-scented marzipans, preserved-fruit conceits, and sugar candies. May uses ambergris primarily in dishes involving eggs or cream or both: eggs poached in syrups, scrambled or poached eggs on toast (a rare non-sweet preparation), rich baked puddings, codling cream (apple fool of sorts), snow cream (a showy whipped-cream conceit), cheesecakes, and the mildly alcoholic hot custard beverage called posset. Manuscript cookbooks trend toward recipes similar to May’s, their most common ambergris vehicles being rich, custardy baked puddings of bread and/or ground almonds, most of which feature dried or preserved fruits (and sometimes sliced apples or cooked artichoke bottoms too), lumps of beef marrow or butter, and plenty of thick cream and eggs. The following recipe is typical except for the “green potatoes whole,” which I am going to guess were the cream-colored sweet potatoes of the day, harvested when tiny and then candied and tinted green to resemble candied citron.

To make Almond Puddings

A Collection of Choise Receipts (New York Academy of Medicine)

Take two pound of Jordan Almonds and lay ym in cold water to Blanch, then beat ym very well wth 3 or 4 spoonfulls of Rose water, Put to your Almonds 3 or 4 ladles full of ye bread soaked in Milk, as for the Bread Puddings, then put in Cream & 7 Eggs, 3 of the whites taken out, Season it wth Sugar, Nutmeg, Orange or Rose water, some Muske and Amber grease—Put in green Potatus whole, & pretty store of Marrow in pieces.

It seems odd to us today that an “animalic” flavor, no matter how subtle, was once favored in rich baked puddings or any other sweet dish. But so it must have been, for musk, too, is animalic, and musk was not only used in most recipes calling for ambergris but also in many recipes on its own—most famously perhaps in the musk sugar candies (or “kissing comfits,” as Shakespeare called them, in reference to musk’s supposed aphrodisiac properties) that the Elizabethan English adopted from Italy and adored for sweets banquets. Whether used singly or in tandem, ambergris and musk were generally deployed in English recipes with rose water and spices—a combination of skanky, racy, and floral scents that sounds to us, rather precisely, like a recipe for perfume. The obvious lesson here is that tastes in seasoning diverge greatly across time—just as they do across cultures. A Dutch-born friend of mine finds the vanilla omnipresent in American foods (nowadays often in extreme concentrations) unpleasant. And I have been told by at least three French persons over the years that the cinnamon met with in American breakfast cereals, doughnuts, yeast breads, quick breads, desserts, and holiday drinks is, to their palates, bizarre and jarring.

In the end, the English predilection for animalic foods proved fleeting. Ambergris and musk appear in few recipes written after 1700. But they do appear in cookbook author E. Smith’s recipe for Whipt Cream (1727), which was copied by Hannah Glasse (1747), and, in turn, by Susannah Carter (American edition, 1772), and finally by Amelia Simmons, our country’s first native-born cookbook author, in her little cookbook of 1796. Served with pastry in the second course of dinner or with cake at evening parties, whipt cream was frothier and more evanescent than our whipped cream, with a winy tang.

Whipt Cream

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery, 1796

Take a quart of cream and the whites of 8 eggs beaten with half a pint of wine; mix it together and sweeten it to your taste with double refined sugar, you may perfume it (if you please) with musk or Amber gum tied in a rag and steeped a little in the cream, whip it up with a whisk and a bit of lemon peel tyed in the middle of the whisk, take off the froth with a spoon, and put into glasses.

One might have expected Simmons to have cut the fragrance from this recipe, as too outré and costly for a cookbook touted on the title page as “adapted to this country and to all grades of life.” But she not only left it in—she almost certainly did so intentionally, for she revised the original “ambergrease” to “amber gum,” which was presumably a colloquial American term at the time. It is just possible that ambergris was in wide culinary use by sophisticated American cooks circa 1800. After all, the precious commodity must have been brought in often by the whalers of the northern Atlantic seaboard, and it probably sold then for considerably less than the price of gold.