By Stephen Schmidt

Plum Pudding, or Christmas Pudding

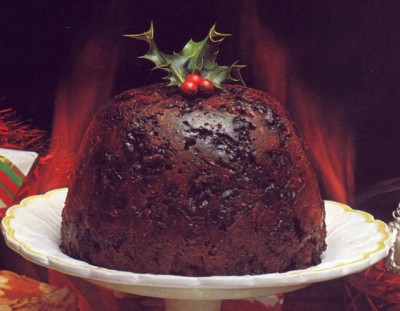

On the evening of November 7, 1862, Catharine Dean Flint staged a formal company dinner for eleven people in her elegant Boston home. An elaborate affair by today’s standards, her dinner included two dessert courses, the first of which featured a plum pudding. When we hear the words “plum pudding,” we visualize a dense, dark, shiny mound that comes to the table dramatically wreathed in brandy flames. The British and Irish still serve plum pudding at Christmas today, albeit under the modern name “Christmas pudding,” but most Americans seem to associate it with English Christmases of the past, most famously, perhaps, that of the Cratchit family in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. It is indeed an old-fashioned pudding, nothing like the cold, creamy desserts that we call puddings today, but rather a sort of dense suet pound cake stuffed with raisins—the “plums.” It is served piping hot, with “rich sauce,” as most puddings once were served.

But this was not, in fact, the pudding that Mrs. Flint served at her dinner on November 7, 1862. Mrs. Flint wrote extensive notes about this dinner, as she did about all of her entertainments, in her manuscript cookbook, which is now in the possession of the American Antiquarian Society, in Worcester, Massachusetts. And in these notes Mrs. Flint remarks, approvingly, that the pudding was served turned out of “the dish in which it was baked.” Classic plum pudding, the kind that comes to the table in flames, is not baked: it is boiled in a cloth bag or, more commonly today, steamed in a ceramic pudding basin or in a fluted metal steeple mold. But American women knew another kind of plum pudding too, which was baked, and it happens that Mrs. Flint’s cookbook contains a recipe for the baked sort of plum pudding—an unusually firm baked plum pudding that proves easy to unmold from its baking dish. The donor of the recipe, “Madam Salisbury,” was likely the mother of Stephen Salisbury II, a frequent guest in the Flint home.

Madam Salisbury’s Plum Pudding

Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (1768-1851), by Gilbert Stuart (courtesy of Worcester Art Museum)

Half a loaf of bread soaked two hours in one quart of milk. Butter the size of an egg. Two heaped spoons of sugar and seven eggs beaten with the sugar and strained on to the bread after it is cold. Pint bowl full of raisins – two tea spoons salt. One even tea spoon cloves a little cinnamon. Bake two hours.

Madame Salisbury’s Plum Pudding

If you are wondering why plum puddings were once so highly esteemed, the simple answer is that, historically, raisins were special. When the English nicknamed raisins “plums” or “little plums” (which happened around the time of the Restoration, in 1660), they were affiliating the fruits with comfits, or dragées, which the English called “sugar plums.” Sugar plums were fancy and festive, and the English, historically, thought the same of raisins, both the large “raisins of the sun” and the small “raisins of Corinth,” which the English called “currants.”1 Writing in 1617, the English traveler and social commentator Fynes Moryson tells us that “the use of Corands of Corinth [is] so frequent in all places, and with all persons in England, as the very Greekes that sell them wonder what we doe with such great quantities thereof, and know not how we should spend them, except we use them for dying, or to feede Hogges.”2 In Moryson’s day, large and small raisins still found their way into many meat, poultry, and vegetable dishes, as they had since the thirteenth century. But the fruits were already beginning to be particularly associated with the many new sweet things then appearing on the scene, including sweet puddings, which were rapidly gaining favor with the English.

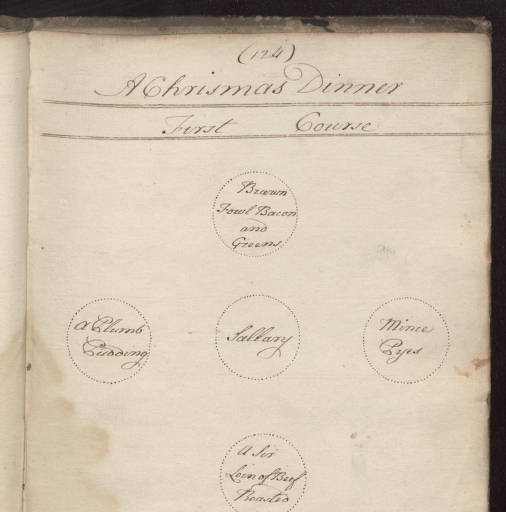

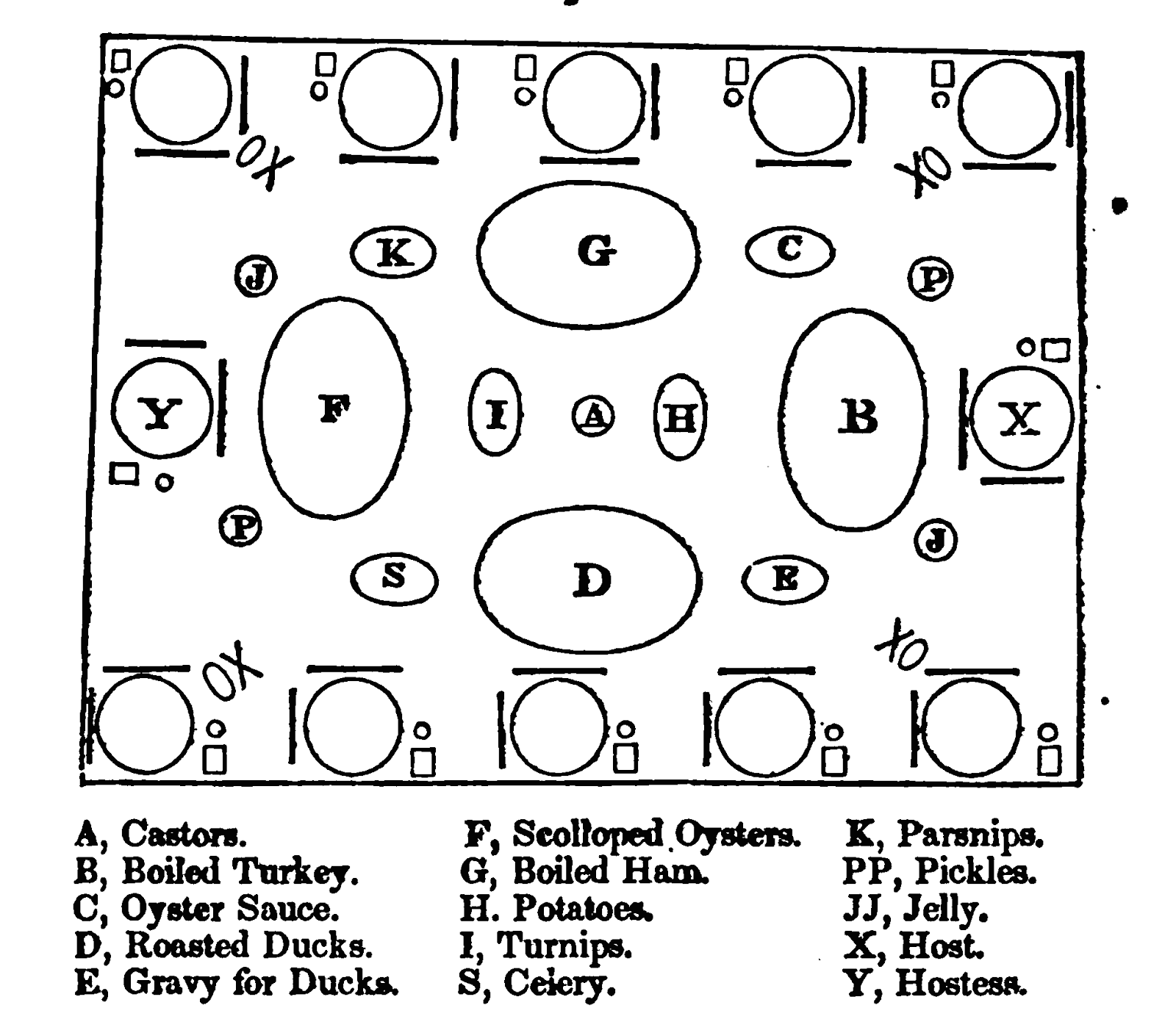

Although based on earlier precedents, boiled plum pudding, so named, did not emerge until the early eighteenth century. Through most of the century, it was, like other puddings, served in the first course of dinner, with the principal meats. And like several other raisin-rich comestibles—such as plum cakes (the ancestors of today’s fruitcakes and British Christmas cakes), plum pottage (a sort of spicy-sweet, fruited beef stew thickened with bread), and mince pie (from which Jack Horner extracted a plum)—plum pudding was a favorite at Christmas. The “Miss Caldwell cookbook, 1757-1790,” an English manuscript in the possession of the University of Iowa, showcases both plum pudding and smallish mince pies in the first course of a Christmas bill of fare, along with two other classics of the English Christmas feast: brawn (cold pickled pork) and “a sirloin of roasted beef.” A number of other English manuscript cookbooks of the period outline similar Christmas dinner first courses.

Miss Caldwell Cookbook Christmas Dinner Bill-of-Fare, First Course, page 124

Boiled plum pudding came to America early on—there are recipes in several eighteenth-century American manuscript cookbooks—and it duly shifted to the second course of dinner in the late eighteenth century, as it did in Britain. Still, American cookbooks imply that the pudding was never as wholeheartedly embraced in this country as in Britain. Harder-pressed American families—families whose circumstances were similar to the Cratchits’—seem rarely to have served it, even at Christmas. And while the American gentry did serve it, sometimes even apart from Christmas and New Year, many gentry cookbooks frame the pudding, in one way or another, as English, as though it were not fully naturalized here. Indeed, starting with Mary Randolph’s The Virginia House-Wife (1824), more than a few American cookbooks title their recipes English Plum Pudding. Perhaps America’s problem with the pudding was its abundance of plums, which made it expensive—or perhaps it was the booze, which many Americans already found objectionable by the 1840s. Or perhaps it was the suet, or beef kidney fat, which had to be cleaned and minced, a fiddly project that English women took in their stride but that American women seem always to have balked at. In addition, many American women no doubt shied away from the six-hour boiling, which someone (preferably “help,” which was always in short supply in America) had to supervise, shifting the pudding in the pot to maintain its round shape and topping up the water as it boiled away. Finally, there was the national “dyspepsia” crisis (or so it was perceived) of the antebellum decades and beyond, during which boiled puddings came to be considered unhealthily “rich” and “heavy.” In The Good Housekeeper, her cookbook of 1841, the redoubtable Sarah Hale warned, “As Christmas comes but once a year, a rich plum pudding may be permitted for the feast, though it is not healthy food; and children should be helped very sparingly.”

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Enter baked plum pudding. Baked plum pudding was essentially a simple bread pudding dressed up a bit: enhanced with plums, obviously (which plain bread pudding in the day did not have), and served hot with a rich sauce (while plain bread pudding was served “cool,” say the cookbook authors, and sauce-less). Baked plum pudding was in multiple ways friendlier to American sensibilities than its boiled counterpart. It had fewer plums than the boiled article and so was cheaper. It did not have booze (except in a very few highfalutin recipes), and while some recipes, in a nod to tradition, do suggest that suet can be used (a dreadful idea, in my view, as suet never melts sufficiently, if at all, in a baked pudding), these same recipes invariably say that butter will do just as well instead, “if you choose.” And most recipes call for butter only—and not for much.3 Even children could be permitted to indulge. And of course there was no six-hour boiling to fret over. An hour or so in an oven (or a Dutch oven) and the pudding was done.

Baked plum pudding shows up in some nineteenth-century British cookbooks, but I do not sense that British women were nearly as fond of it, or as reliant on it, as American women were.4 Here it became not only an “every woman’s” alternative to boiled plum pudding on holiday tables but also, as Mary Cornelius tells us, an all-purpose company treat that could be served either as a dessert or as a tea cake. In the 1859 edition of The Young Housekeeper’s Friend, Mrs. Cornelius advises her readers:

These puddings are served with a rich sauce, if eaten warm, but are excellent cold, cut up like cake. People that are subject to a great deal of uninvited company, find it convenient in cold weather to bake half a dozen at once. They will keep several weeks, and when one is to be used, it may be loosened from the dish by a knife passed around it, and little hot water be poured in round the edge. It should then be covered close, and set for half an hour into the stove or oven.

Mrs. Cornelius provides two recipes for baked plum pudding. Her first recipe, she says, can be made with soda crackers rather than bread, in which guise it was often called cracker pudding. Most nineteenth-century American cookbook authors have a recipe for cracker pudding, including Fannie Farmer, who features it in her Thanksgiving menu under the name “Thanksgiving Pudding.” Mrs. Cornelius’s second recipe is thus:

Soak a pound of soft bread in a quart of boiled milk till it can easily be strained through a coarse hair sieve; then add seven eggs, two gills of cream, a quarter of a pound of butter (melted), a gill of rose-water, or some extract of rose, a little cinnamon or nutmeg, and a pound of raisins. For a small family, bake it in two dishes, an hour; and reserve one for another day.

Students of historical American cooking may think that they have seen this recipe somewhere else—and indeed they have. It is a paraphrase of the recipe called “A Bread Pudding” outlined by Amelia Simmons in American Cookery (1796), our nation’s first homegrown cookbook. As I’ve said, historical American bread pudding did not have plums, so Simmons’s title is something of a mystery.

Amelia Simmons’s A Bread Pudding

A Bread Pudding

One pound soft bread or biscuit [crackers] soaked in one quart milk, run thro’ a sieve or cullender [colander], add 7 eggs, three quarters of a pound sugar, one quarter of a pound butter, nutmeg or cinnamon, one gill rosewater, one pound stone raisins, half pint cream, bake three quarters of an hour, middling oven.

It turns out that Catharine Dean Flint copied Simmons’s recipe verbatim into her manuscript cookbook, so it may have been Simmons’s baked plum pudding, not Madam Salisbury’s, that Mrs. Flint served at her dinner of November 7, 1862. Which is better? I would give the edge to Simmons’s pudding, which is sweeter, richer, and softer than Madam Salisbury’s and has the lovely flavor of rose water (which, despite the large quantity, is subtle). Still, Madam Salisbury’s pudding slices beautifully and has an appealing spicy flavor, and it is sweet enough if you interpret her “two heaped spoons of sugar” liberally. Adapted recipes for both puddings can be found here. Those fortunate to be subject to a great deal of company, uninvited or invited, over the holidays may find it convenient to have at least one in reserve.

[NOTES]

- Currants, the berries, came to England in the sixteenth century. Initially, some English mistakenly believed that the berries, when dried, made raisins of Corinth. And so the berries, too, became “currants.” ↩

- William Brenchley Wrye, England as Seen by Foreigners in the Days of Elizabeth and James I (London: John Russell Smith, Soho Square: 1865), 190. Retrieved December 3, 2016 from Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/englandasseenbyf00ryew ↩

- While classic boiled plum pudding requires an equal weight of fat to bread (and/or flour), baked plum pudding has only a quarter weight of fat to bread or less. ↩

- My hunch is that American baked plum pudding and British baked plum pudding evolved (fairly) independently. The American and British recipes differ in some details, and the uses of the recipes, as implied in the cookbooks, are also different. ↩

![Boston, Massachusetts 1860 City Directory Page 152, which lists Flint, Waldo, pres. Eagle Bank, 16 Kilby, h. [house] 6 West](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2016-4-23-152-181x300.jpg)

foods comprised a whole ham and four chickens. Another supper featured the same cold dishes plus lobster salad, and another tempted guests with four cold chickens with “celery dressed” and four cold geese (a rather strange idea, at least to most people today). The cold foods were paired with an equally bountiful array of hot items. At most suppers, Mrs. Flint served three or four hot ducks plus four hot grouse or partridges, though at one supper she offered instead a turkey (with deep-fried mashed potato balls) and six roasted pigeons. I suspect that the turkey was boiled, and that the grouse and partridges served at the other suppers were boiled too. The many hot birds on these menus would not all have fit in a period stove oven, and boiling was then a common way to cook poultry, at least of certain types.

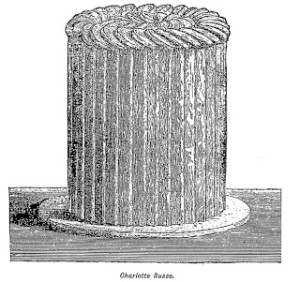

foods comprised a whole ham and four chickens. Another supper featured the same cold dishes plus lobster salad, and another tempted guests with four cold chickens with “celery dressed” and four cold geese (a rather strange idea, at least to most people today). The cold foods were paired with an equally bountiful array of hot items. At most suppers, Mrs. Flint served three or four hot ducks plus four hot grouse or partridges, though at one supper she offered instead a turkey (with deep-fried mashed potato balls) and six roasted pigeons. I suspect that the turkey was boiled, and that the grouse and partridges served at the other suppers were boiled too. The many hot birds on these menus would not all have fit in a period stove oven, and boiling was then a common way to cook poultry, at least of certain types.  Seemingly patterned after the fancy new dinner service called à la russe, the final courses of the suppers were incredibly lavish. On February 2, 1860, Mr. Flint’s twelve guests were confronted with one quart of charlotte russe, one quart of frozen pudding, three pints of Roman punch, three pints of vanilla ice cream, and two one-quart molds of calves’ foot jelly

Seemingly patterned after the fancy new dinner service called à la russe, the final courses of the suppers were incredibly lavish. On February 2, 1860, Mr. Flint’s twelve guests were confronted with one quart of charlotte russe, one quart of frozen pudding, three pints of Roman punch, three pints of vanilla ice cream, and two one-quart molds of calves’ foot jelly