By Stephen Schmidt

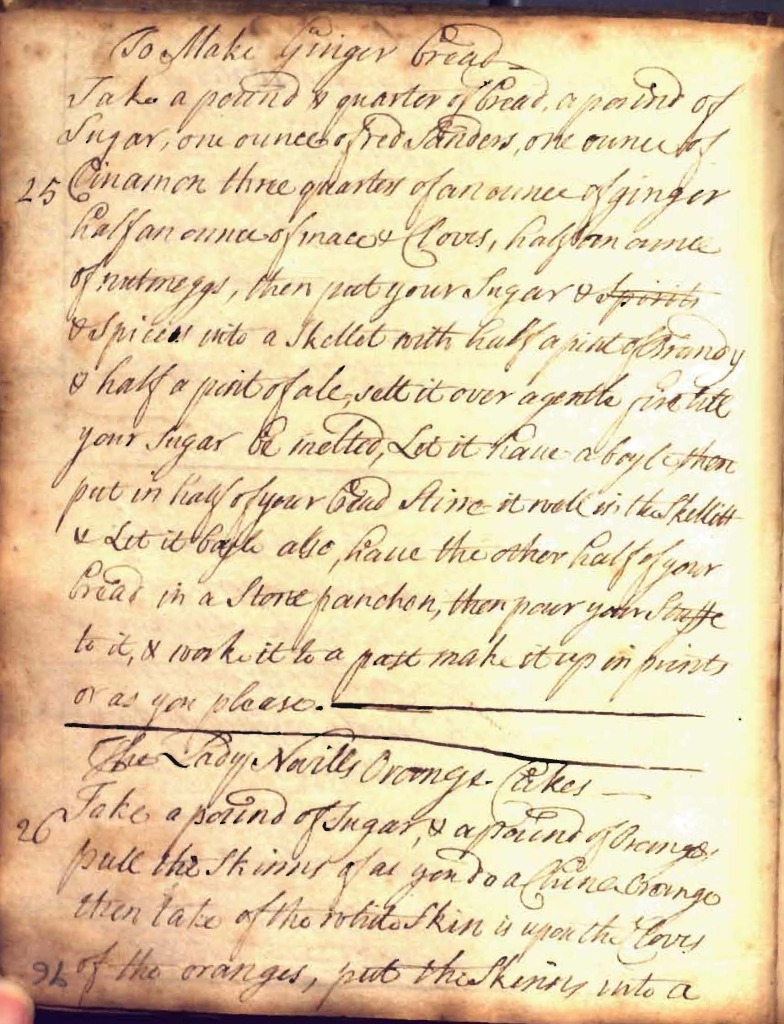

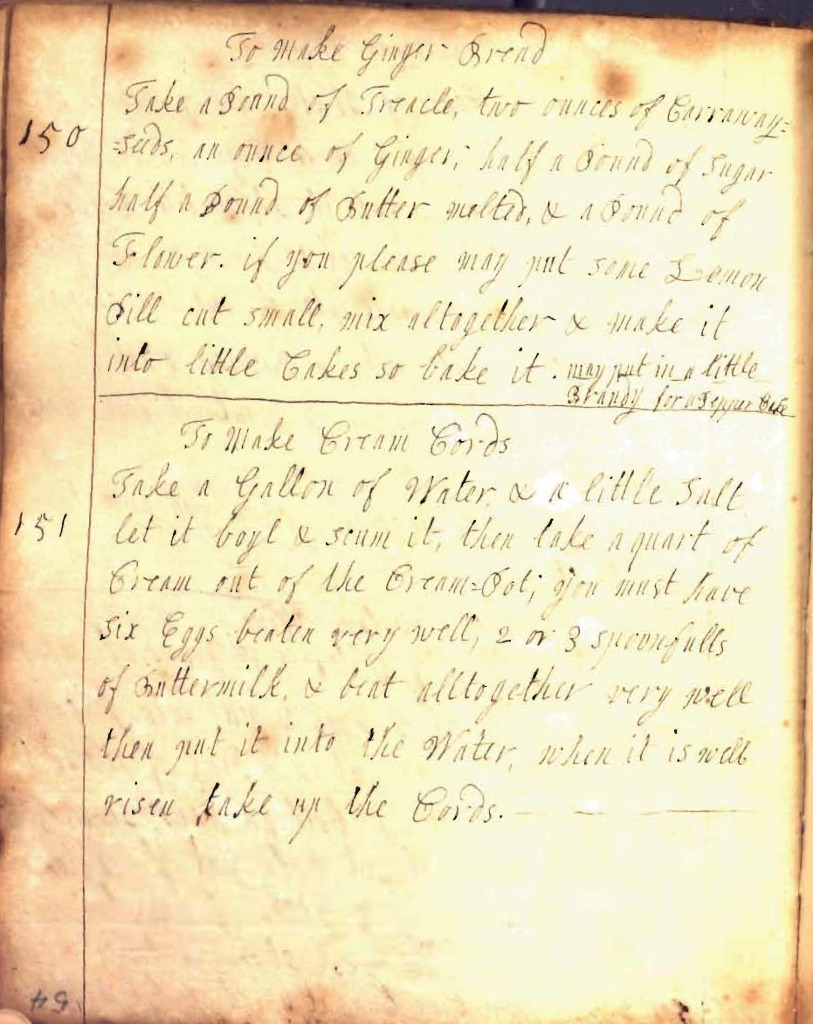

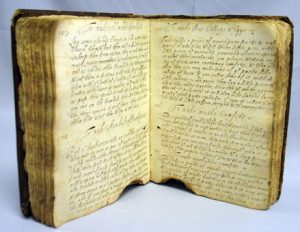

Martha Washington manuscript, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

One evening last November, the Culinary Historians of New York sponsored a panel discussion on the work of culinary historian Karen Hess, in celebration of her 100th birthday. Karen Hess, who died in 2007, came into public awareness with the publication of The Taste of America, in 1978, which she wrote with her husband John Hess. The book became notorious for its caustic, sometimes unfair attacks on the era’s bestselling historians and food luminaries. But its basic argument—that the quality of American cooking, far from improving over the centuries, had actually declined—was compelling. To make their case, the Hesses drew on hard evidence in the form of historical recipes, which they quoted, visualized step-by-step, and, in some instances, seem to have made. To the extent that historical recipes reveal what people of the past actually cooked and ate—a fraught question, I realize—the Hesses’ argument seemed incontrovertible.

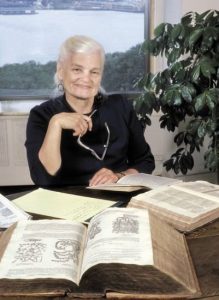

Karen Hess

Younger people may find it hard to believe how revolutionary such an approach was at the time the Hesses published. In 1979, when Barbara Wheaton, author of the groundbreaking Savoring the Past (1983), wrote about her experience in preparing a roasted peacock redressed in its plumage for a medieval banquet, many people thought she was daft. Culinary history, especially American culinary history, was then almost exclusively treated as a popular subject, mostly in works that were essentially cookbooks expanded to include some historical material. Few writers of these works even cited historical American recipes, much less attempted to make them. And those few who did recreate historical dishes, or claimed to, professed varying measures of befuddlement, amusement, and alarm at the recipes’ instructions, which obliged them to “adapt” the recipes more or less to point of erasure. Many mid-twentieth-century popular evocations of the American past seem sentimental, patronizing, and biased by today’s standards, but evocations of historical American cooking seem shockingly so. Books that dealt with historical cooking dished it up as quaint and fun but ultimately just old-timey women’s work—a subject that no one could take entirely seriously.

Martha Washington manuscript, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Very much of its time is Marie Kimball’s The Martha Washington Cook Book (1940), which purports to elucidate the meals and entertainments of George and Martha Washington, as revealed by a handwritten cookbook that Martha Washington owned and eventually passed down to her granddaughter. Kimball tells us that this cookbook was authored by Martha Washington’s first mother-in-law, Frances Parke Custis, and comprises “a collection of the favorite dishes and ‘rules’ of the Washington household.” Actually, the manuscript was compiled by an unknown person of a privileged English family around 1675, and was subsequently brought to this country by unknown means, whereupon it somehow fell into Martha Washington’s hands. The first lady is unlikely even to have recognized most of the recipes, much less used them, because by the time she married her first husband, Daniel Custis, in 1750, the Restoration-era cooking that the manuscript outlines was thoroughly outmoded. The bulk of Kimball’s book comprises over one hundred pages of recipes supposedly culled from the manuscript. “It has been necessary, of course, to make some adaptation” of the recipes, Kimball writes, since the recipes yield “appalling” quantities, and “some of the recipes are scarcely in accordance with modern taste or practice.” Kimball’s ignorance of the recipes is almost hilarious, as when she defines “suckets of long bisket” as “a variety of crouton.” (They were long comfits, perhaps of candied citrus peel.) In any event, “some adaptation” is a considerable understatement. A number of the recipes appear to be simply Kimball’s own creations. Others bear titles and some random ingredients imported from the manuscript’s recipes but produce entirely different dishes, invariably bad ones. At the end of her recipe for Quince Pie, an utterly bowdlerized version of a recipe that does appear in in the manuscript, Kimball suggests omitting the pie’s top crust in favor of a topping of whipped cream. “Martha Washington did not do this,” Kimball writes in all seriousness—as if Martha Washington, much less the actual author of the book, did any of this.

In 1980 Karen Hess published Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery, her first solo book and arguably her masterwork. The book is not a riposte to Kimball’s, which Hess does her best to “ignore,” but it does, by its brilliant example, expose the attitudes that underlay Kimball’s book and the many others like it, as well as the misconceptions that these books promoted. Hess presents a verbatim transcription of the Martha Washington manuscript, with commentary following each recipe, in which she explains unfamiliar terms and procedures, fills in gaps in the recipe’s instructions, describes the recipe’s variants, antecedents, and later forms, and explores the recipe’s possible meanings to the people who created it. In some instances she submits recipes to trial and reports her results. In the end, we gain a concrete sense of how one privileged Restoration English family cooked and ate, knowledge that is crucial to us because, as Hess states, English cooking is the “warp and weft” of our own. This is more obviously apparent in American cookbooks written before the Civil War, which are replete with recipes copied verbatim from English works, but it is still true today, even as myriad diverse culinary influences have been brought to bear on our daily cuisine. Bacon, barbecue, ham, meatloaf, macaroni and cheese, candied sweet potatoes, sandwich bread, ketchup, biscuits, muffins, cornstarch puddings, fruit pies, sweet potato pie, lemon meringue pie, and butter cakes all have links to historic English cooking. And that is hardly an exhaustive list.

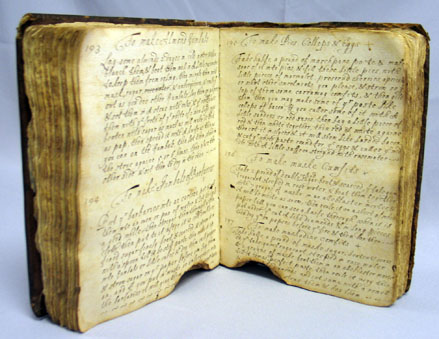

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery, by Karen Hess

Today, many culinary historians ground their work in the close study of historical recipes, following the example of Karen Hess, Barbara Wheaton, and other pioneering recipe scholars. But the unhappy truth is that much of the culinary history most visible to the public follows in the tradition of Marie Kimball’s book: mangled “adaptations” of historical recipes falsely presented as a “taste of the past.” The enormous public interest in food now impels all sorts of people to adapt historical recipes, some for their own purposes, and some for the purposes of an organization that employs them. In effect, historical recipes have become a tool of business in the broadest sense of the word, and when the claims of business and scholarship compete, business usually wins. Meanwhile, the hive of this activity is cyberspace, where historical recipes, like everything else, are dragged through the muck of blithe ignorance, self-dramatization, unrelenting solipsism, vulgarity, and shameless pandering endemic to the realm. ‘Truth is the debt we owe to the dead,’ said Voltaire, supposedly, but the only debt many online adapters owe is to their own interests. They profess to “update” historical recipes toward the end of making them more palatable, or more healthful, or more practical to cooks today, when they are actually rewriting the recipes from top to bottom. It is galling when these persons claim or imply that their handiwork serves some historical purpose. But there is no point in fulminating against these bad recipes—Karen Hess’s fulminations got her nowhere. The more useful response is to ignore them and create better work.

And that is what many of today’s online historical recipe adapters would like to do, if they only knew how. Herewith I offer some tips on the endeavor for the benefit of non-specialists. I will focus on the fine seventeenth-century English cuisine outlined in the Martha Washington manuscript, but my advice applies to historical Anglo-American cuisine of any period.

2.

Let’s first set the terms—at least as I see them. As Karen Hess acknowledges, in adapting historical recipes for today’s cooks, revisions are sometimes unavoidable—and they are fine as long as they respect the intentions of the original recipes. For example, Karen disliked the “sliced nutmeg” called for in many seventeenth-century recipes. I don’t mind it, but I don’t think you would be violating a recipe if you grated the nutmeg instead. Many seventeenth-century puddings made with a pound of butter taste little different when made with only half as much. Likewise, some of the dozen or more ingredients called for in a seventeenth-century “pie of many things” can be omitted—indeed some, such as cow’s udder or cockscombs, must be. But there is a difference between updating a historical recipe to make it feasible—and updating it to the point that it becomes a contemporary recipe with old-timey affectations. If you puff up a batch of Portugal cakes with baking powder, which people of the day had never heard of and would have regarded as an adulterant if they had, you cannot call your recipe Portugal cakes. Likewise, if you decrease or omit the sugar in the pungently spiced, syrupy-sweet banqueting wine called hippocras, you are no longer making hippocras. Hippocras was a medicinal wine, and in the medical thinking of the day, the sugar it contains was an indispensable drug, both unleashing the curative properties of the spices and conveying a potent cure of its own.

That said, let’s proceed. I will assume that you already have a particular seventeenth-century recipe in your sights and that, if it is a manuscript recipe, you have already transcribed it verbatim. I now present my process of adapting historical recipes in four steps.

Step One: Look at Multiple Contemporaneous Recipes for Your Dish or Conceit

Before you can adapt a seventeenth-century recipe, you need to discover what your recipe is telling you. And you also need to discover anything that your recipe is not telling you but that you need to know in order to recreate the dish in modern terms with reasonable faithfulness. The quickest and surest way to make this discovery is to examine a number of contemporaneous recipes for the dish or conceit you are working with. Whatever is unstated, unclear, unknown, or possibly erroneous in your particular recipe will likely be elucidated in others.

Examining multiple recipes will often reveal the meaning of strange words and phrases in your recipe that are not defined online or in any dictionary. I think most contemporary readers will be stumped, as I once was, by the term “hard lettuce,” which turns up in a dozen recipes for so-called “boiled meats” and meat pies in Hannah Woolley’s The Queen-like Closet (1681). If you patiently page through all of Woolley’s recipes for boiled meats and meat pies, towards the end of the book, you will finally come to a recipe titled “To boil Chickens with Lettuce the very best way,” which reveals what hard lettuce is. The crucial sentence reads, “Take good store of hard Lettuce, cut them in halves, and wash them . . .” Lettuces that can be cut in halves through their hard cores are head lettuces, like today’s Boston or Bibb lettuces—as opposed to leaf lettuces, the kind that make up mesclun. A few pages further on, your new-found insight is corroborated by the recipe “To make a Lettuce Pie.” The crucial sentence here reads, “Take your Cabbage Lettuce and cut them in halves.” A cabbage lettuce, obviously, is a lettuce that looks like a cabbage because it grows in a head. In the course of perusing multiple recipes, you will also begin to pick up seventeenth-century culinary language. “Boil” usually means simmer; “sifted” often means grated; “temper” means mix; meats can be “fried” in wine or water; and “bake” does not always mean in an oven. “Gravy” is the juice that runs from rare-cooked meat, and “sauce” can mean an elaborate garnish that is practically a separate dish.

Cracknels, A Collection of Choise Receipts, 1680 [manuscript], New York Academy of Medicine

Old-Style Cracknels, John Murrell, A Deligtfull Daily Exercise (1623)

I will add a caveat. A cracknels sleuth may come across a recipe that says to form cracknels in the shape of a cup or bowl and immerse them in boiling water before baking them. These alarming instructions do not indicate an unsuspected elision in the many other cracknels recipes that the sleuth has perused. Rather, they pertain to an older, pan-European form of cracknels that remained current for several decades as modern, distinctively English cracknels evolved. If you suspect a like complication in the dish you are working with, you should search the dish in sources predating and postdating the source of your recipe. There are not many such recipes, thank goodness. More often, recipes follow different patterns because the dish was extant in variations. Most seventeenth-century English fricassees, for example, are “white” because the meat is “fried” in liquid, which is to say, it is actually poached. However, there are also fricassees that entail true frying (as the French word “fricassee” connotes), resulting in browned meat in a brown sauce. (These fricassee variations persist to this day.) Likewise, most of seventeenth-century banqueting creams exist in variants with respect to the manner of thickening, whether by heat, acid, rennet, gelatin, whipping, churning, or some combination. Recipes for “Portugal eggs” and “Spanish eggs” are crazily variable for a unique reason. The terms came to denote several quite different Iberian sweet egg dishes that presumably were brought to England by Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese queen consort of King Charles II—as well as far-flung variations on these dishes dreamt up by English cooks.

Eggs in the Portugal Fashion, Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (1665)

Eggs the Portugal Way, John Nott, Confectioners’ Dictionary (1723)

Eggs the Spanish Way, John Nott, Confectioners’ Dictionary (1723)

A final caveat: There are some things you will never discover no matter how many recipes you look at. What, for example, is that “bundle of sweet herbs” that turns up in recipe after recipe? Sweet herbs comprised most of the common herbs in use today, except for basil and tarragon. But did certain dishes generally take more of some sweet herbs and less of others, as is true today? We will likely never know.

Step Two: Adjust for Seventeenth-Century Ingredients and Cooking Technologies

Many seventeenth-century recipes call for ingredients that are now hard to find or unavailable. For some of these you can suggest substitutes: candied chestnuts for candied eryngo roots; lemon juice for verjuice; granulated yeast plus water for ale yeast (I’ll discuss equivalents in my next blog post); a sweet orange and a lime for two bitter oranges (as nineteenth-century cookbook author Eliza Leslie does in making orange pudding). Others such as pickled samphire, certain organ meats, and ambergris and musk must be omitted. Omissions do not matter much unless there are many of them or they are the principal feature of the dish, as in a mugget pie (bovine umbilical cord). In that case, you need to move on to another recipe.

A more important ingredient consideration is discrepancies between old and modern foodstuffs. Some of these are clear-cut. Cream and milk were raw and reacted differently to heat, acid, and whipping than our pasteurized product. (A few banqueting creams and syllabubs are impossible to reproduce for this reason.) A dozen seventeenth-century eggs weighed around one pound, while it takes only eight of today’s “large” eggs to weigh as much. Thus the eggs called for in a seventeenth-century recipe should be reduced by about one third in an adaptation. (Sometimes the arithmetic is awkward and you will have to approximate.) Other discrepancies are hazier. I assume that, like eggs, seventeenth-century farm-raised meats, fruits, and vegetables were around a third smaller than ours. I confess that I don’t actually know anything about seventeenth-century animal breeds, and I should ask people who do. (There are some.) The typical size of seventeenth-century fruits and vegetables is probably anybody’s guess. Also a guess is the taste and texture of seventeenth-century meats and produce. Karen Hess believed their flavor was more intense, but I think this may be a sentimental generalization. Revived varieties of “heirloom” apples often prove to be dry, sour, woody, and generally unpleasant. Since you cannot know these things there is no point obsessing over them.

Wheat flour presents special complications. Seventeenth-century English wheat flour had less protein than our all-purpose flour and was therefore less absorptive, despite the specks of germ and bran likely present in even “the finest white flour,” which had the opposite effect. Thus in adapting recipes, relatively low-protein all-purpose flours, such as Gold Medal and Pillsbury brands, are wiser choices than Hecker’s or King Arthur, which are very nearly bread flours even though they are labelled “all-purpose.” I start be adding whatever quantity of flour the original recipe calls for and hope that the dough or batter will cooperate. If it doesn’t, I make adjustments. Unfortunately, absorption is not the only wheat-flour issue. When a recipe specifies flour by a volume measurement—that is, a peck, a gallon, a quart, or a pint—the recipe may intend the understood weight of the flour when measured by the old dry peck, which was 14 pounds (and thus 7 pounds to a gallon, 1 3/4 pounds to a quart, and 14 ounces to a pint). Or the recipe may intend the volume of the flour when measured by the ale or wine quart, which was the same as the modern American quart: 32 cups to a peck,1 16 to a gallon, and 4 to a quart, and 2 to a pint. There is a big difference between the dry-peck weight and the liquid volume measure. While a quart of flour by the peck weight is 1 3/4 pounds, a quart of flour by liquid volume is only 1 to 1 1/4 pounds depending on how settled the flour is in the measure. In adapting old recipes, Elizabeth David hews to the peck weight (which she reckons at 12 pounds, yet another complication!). Karen Hess adapts by the liquid quart. They are both right. Seventeenth-century cooks followed both systems. A few recipes specify the system to be used, stating “by weight” or else giving the measure in “ale pints” or “wine quarts.” And sometimes you can deduce the system from context, as you can in Constance Hall’s extraordinary helpful 1672 table of pastry recipes. If your recipe provides no explicit clues, begin adapting by volume. If your dough turns out to be soup, you know that the original recipe meant weight.

Finally, unless you happen to be a hearth cook, you cannot know the particular tastes and textures of foods cooked at the fireplace using seventeenth-century cooking equipment. Karen Hess claimed that meat roasted in or in front of a fireplace attained a fabulous thick, dark crust, while meat roasted in a gas or electric oven emerges gray and steamy. Perhaps she was right. Nineteenth-century American cookbooks show that some households continued to roast meat in the fireplace many decades after they had otherwise given up cooking at the hearth in favor of the stove. But whether or not fireplace-roasted meats were superior, there is no point in trying to replicate them in a modern stove oven because it cannot be done. And in case you regret being unable to reproduce the taste of smoke in your adapted recipe, don’t. Seventeenth-century fireplace foods did not taste of smoke, or at least were not meant to. I have read that fireplace-cooked meats tasted delightfully “barbecued” or “grilled” and that hearth breads like muffins tasted smoky. This is nonsense.

Step Three: Check Your Adaptation for Modern Biases and Assumptions

I am assuming that by now you have a draft of your adapted recipe before you. Now you must ruthlessly examine it for any modern biases or assumptions that you may have brought to it. I am particularly prone to importing modern notions into an adapted recipe when attempting to wriggle out of something in the original recipe that I don’t want to do—like boiling turnips or spinach for an hour, or using the entire “peel” of a lemon or orange (including the bitter white pith), or deliberately curdling eggs (even when I know that curdling is the point, as in a posset or certain cheesecakes). You may also be led astray by some insidious miscue embedded in the recipe. A recipe titled “in the French style” may tempt you to cram your adaptation with butter, or drown it in wine, or shower it with herbs, or somehow make it “fancy.” These are all mistakes. Whatever “French” connotes in your recipe, it does not connote what it does today. The same is true of recipes described as “Italian,” “Dutch,” or “Spanish.” The same goes for “best” and “newest fashion.” These terms could mean anything—or possibly nothing other than the egotism or marketing eagerness of whoever wrote the recipe. Think of how many recipes today are touted as “best,” “ultimate,” “perfect,” “the only recipe you need,” or whatever. Whether or not we today understand the rationales behind such boasts (and often we don’t), we can be certain that culinary historians three hundred years from now won’t have a clue.

Especially insidious are those seventeenth-century recipes that go by names familiar today, such as stew, roast, pudding, pie, tart, pasty, biscuit, custard, and cake. Although the names are the same as ours, the dishes are quite different. Sometimes we don’t grasp these differences, and sometimes we do, at least sort of, but they seem so wrong to us that we smudge them over with our own notions when adapting the recipe. The following recipe from Hannah Woolley’s Queen-like Closet tempts me to fall into this particular pit, although I hope to have avoided doing so in my (untested) adaptation.

Hannah Woolley, frontispiece of “The Gentlewoman’s Companion” (1673)

To stew a Loin of Mutton

Cut your meat in Steaks, and put it into so much water as will cover it, when it is scummed, put to it three or four Onions sliced, with some Turneps, whole Cloves, and sliced Ginger, when it is half stewed, put in sliced Bacon and some sweet herbs minced small, some Vinegar and Salt, when it is ready, put in some Capers, then dish your Meat upon Sippets and serve it in, and garnish your Dish with Barberries and Limon.

To Stew a Loin of Mutton (adapted)

Have your butcher cut a side of lamb loin into six chops. Arrange the meat in two or three overlapping layers in a large pot with 2 medium onions, sliced, 3 peeled and quartered white turnips, 6 whole cloves, and 2 tablespoons thinly sliced peeled ginger. Add enough water to cover the ingredients, bring to a boil over high heat, and then turn the heat down to the point where the water gently simmers. Cook for 30 minutes, periodically skimming off any gray foam that rises to the top. Add 3 slices bacon, cut in 1-inch pieces, 1 or 2 tablespoons each minced thyme and rosemary, 1/4 cup white wine vinegar, and sufficient salt to season, probably about 1 tablespoon. Cover the pot, turn down the heat very low, and cook until the meat is very tender and nearly falling off the bone, 30 to 60 minutes longer. Add 1/3 cup large capers, rinsed of salt or brine. Cover a large, deep platter with thinly sliced white bread that has been dried in a slow oven until crisp through and through. Arrange the meat and vegetables on the bread and then, a little at a time, ladle on as much of the broth as the bread will absorb and the platter will hold. Strew the meat with scalded cranberries and thin lemon slices.

Like most historical recipes, this recipe requires some substitutions (for the mutton, seventeenth-century bacon, and barberries; it’s conceivable that Woolley’s ginger was fresh) and some guessing about quantities. But the more serious problem is that the dish runs counter to our expectations of a stew. We would brown the meat, and we would cook it in stock and/or wine. And, at the end, we would reduce the cooking medium and perhaps also thicken it with flour and butter, making a rich sauce or gravy. But that is not how seventeenth-century cooks typically made a stew. Recipe after recipe yields the same sort of dish that Hannah Woolley’s recipe does: boiled meat in a mildly acidulated broth served on dry bread. Robert May succinctly conveys the character of the dish when he writes, in his recipe for stewed lamb’s head, “serve it on carved sippets and broth it.” With a recipe such as this, we are liable to read right past the actual instructions and adapt the recipe as we would prefer it—and that would hardly constitute a “taste of the past.” For all I know, this dish may be more interesting than it reads on the page, although I confess that I am not eager to try it. If, for some reason, I absolutely had to adapt a period stew recipe, I would search for an outlier recipe that better conforms to modern stew standards. Robert May has one in The Accomplisht Cook (1665): Stewed Collops of Beef.

Your adaptation is now done. You know what the original recipe says and you have written what it says in modern terms. But before you test the adaptation in your kitchen, you need to ask yourself if everything your adapted recipe says to do is actually practical for today’s cooks. If it is not, you may decide to revise your adaptation at least slightly, even though this will likely mean changing the original recipe’s intent. How much you can change a historical recipe in your adaptation and still legitimately claim your adaptation as “a taste of the past” is a case-by-case decision. I offer the following test case.

Step Four: Make Judicious Practical Revisions in the Recipe before You Test It

The following recipe for a Dutch Pie is from “Cookbook of Ann Smith, 1698,” at the Folger Shakespeare Library. For the pastry, I used a recipe in Queen-like Closet (1681), by Hannah Woolley. Ann Smith’s recipe provides uncommonly precise ingredient quantities, probably because the dish is unusual (this is the only recipe I have seen), with an unusually high seasoning, and so a period cook could not wing it based on past experience.

To Make An Excellent Dish Called A Dutch Pye

Take A spesiall brest of Veale bone & roll Beaten & Lett it be seasoned 6 houres with these Following things Viz: 1/2 oz of nutmegs 1/2 oz of cloves & mace ye greatest part to mace & 2 oz of pepper one of them beaten & 2 large rasess of Ginger and 2 handfulls of Marjorum & Thyme and a handful of Salt the Like of sorrill & A Lemon ye rinde shread small & the juce Squezed in: all thesse must be well Beaten & mixed in together & 4 Anchoivess 1/4 of a pinte of white wine 3 Spoonfulls of venigur 3 youlks of eggs: The Venigur ye wine the eggs Beaten together & putt into yor meate Just before itt goes into the Paste, The other seasonings is to be putt in 6 houres before & putt into the Bakeing 3 lb of Butter & Cover itt over with Butter itt must be 4 houres A Bakeing att the Leastt The most Natturall way is to Eatt itt Cold.

To Make a Pasty of a Breast of Veal

Take half a peck of fine Flower, and two pounds of Butter broken into little bits, 1 egg, a little Salt, and as much cold Cream, or Milk as will make it into a Paste; when you have framed your pasty, lay in your Breast of Veal boned . . . .

To Make An Excellent Dish Called A Dutch Pye (adapted)

Remove the bones from a small half veal breast weighing 5 to 6 pounds. In a medium bowl, stir together 1 tablespoon grated nutmeg, 1 1/2 tablespoons ground ginger, 2 teaspoons ground mace, 1 teaspoon ground cloves, 2 tablespoons ground black pepper, 2 tablespoons whole black peppercorns, and 1 1/2 tablespoons fine-textured salt. Add the finely minced peel of 1/2 small lemon (including white pith), 1/4 cup chopped sorrel (or 1 tablespoon vinegar), about 2 tablespoons each chopped marjoram and thyme leaves, and 2 mashed anchovy fillets or 1 tablespoon anchovy paste. Spread this mixture evenly over the bone side of the veal breast and then roll the veal breast up. Refrigerate in a covered container for at least 6 hours or up to a day if more convenient.

Combine 30 ounces all-purpose flour (about 6 cups) and 2 teaspoons fine-textured salt in a large bowl. Have ready 24 ounces unsalted butter, softened to a clay-like consistency. Cut the butter into thick pats and rub it into the flour with your hands until it mostly disappears. In a small bowl, beat together until well combined 2 large eggs and 1/2 cup cold milk. Using a large spoon or rubber spatula, stir this into the flour/butter mixture until the dough gathers and then knead the dough in the bowl until smooth and cohesive.

Cut off one third of the dough (or 1 pound) and set aside. Roll the remainder into a 16-inch round on a well-floured work surface. Fold the dough in half, transfer it to a buttered 10- X 3-inch spring-form pan, unfold it to cover the bottom and side of the pan and then press it into place, flattening pleats in the wall and smoothing or patching any tears. Press the wall all around with your fingers to make it extend about 1/4 inch beyond the top of the pan. Fit the meat inside the crust. Beat together 1/4 cup white wine, 3 tablespoons vinegar, and 1 egg yolk. Pour this over the meat. Scatter 6 to 8 ounces butter, cut into bits over and around the meat. Roll the reserved dough into a 10 1/2-inch round. Place it over the top of the pie and press the edges of the bottom and top crust together with your fingers to seal. Trim the edge if necessary and flute. Cut four 1-inch slits at right angles in the center of the top crust to allow steam to escape. Place the pie on a rimmed baking sheet. Bake in the lower-middle level of a 325-degree oven for 4 hours.

In my adaptation, I cut all ingredients by half, and I guessed, as I had to, what is meant by “2 large races of ginger” (these are dried gingerroots), a “handful,” and a “spoonful.” I didn’t have sorrel and suspected that most people wouldn’t either, so I suggested replacing it with a little vinegar. The crust of this pie has to be thick, sturdy, and rather deep in order to hold the large piece of meat and the three pounds of butter. Since this pie bears a general similarity to a pasty, I thought it was justifiable to adapt it with a typical crust for a pasty, which has the advantage of being thick, sturdy, and also edible, unlike many of the thick, sturdy crusts for meat pies in the day. These adaptations, in my view, are minor, but I did significantly revise the original recipe on two points. The crust for this pie would likely have been “raised” with the hands, at least partially, and the pie would have been baked freestanding on a flat tray. I don’t trust myself to do this, and I doubt that most cooks today would want to try. So I rolled the crust with a pin and I baked the pie in a spring-form pan, whose sides and bottom can be removed after the pie is baked, providing the illusion that no pan was ever involved.

I have no reservations about how I handled the crust, but I am slightly less comfortable about my revision of the butter. I found the quantity of butter called for in the original recipe scary, and I did not see the point, so I adapted the pie with only a quarter as much. After I had tasted the pie (which was lovely and not nearly as spicy as I had expected), it occurred to me that if the meat had baked ‘covered over with butter,’ as the original recipe says, it might have had a different texture, like that of a confit or potted meat. And it dawned on me that possibly the purpose of the seemingly outrageous quantities of butter called for in many meat pie recipes of the period is precisely to make the pie meat long-keeping, in the manner of a confit. There is evidence that these pies were served and stored and then served again and stored again over a stretch of weeks. The only way to know if the full complement of butter promotes a different taste and texture in the pie is to try the recipe as written. Perhaps someday I will. And if the butter does prove to make a significant difference (and does not invite a butter-fueled oven fire or some other catastrophe), I may suggest that intrepid cooks consider trying the recipe that way.

A final word: I really liked this pie. But I don’t like every old recipe I test, and it is very hard for me to give up on a recipe that I’ve brought to the point of testing. Sometimes I don’t have to. For example, if I dislike a recipe I’ve tested simply because it has too much mace, I don’t have qualms about retesting it with less, especially if other recipes for the same dish call for less mace or indeed none at all. But sometimes I dislike an old recipe on multiple counts and I cannot possibly justify all the revisions I would need to make in order to make it palatable. When this happens to you, don’t torture yourself struggling to turn an unappealing historical recipe into a modern recipe you like. Just move on to another recipe.

What, if anything, do we really learn from recreating historical dishes?

One of the highlights of my undergraduate years was a poetry seminar I took with Adrienne Rich. She passed on to us three questions that a crusty, old professor of hers said should be asked of any piece of writing: What did the writer set out to do? Did the writer do it? Was it worth doing? The same questions can be asked of historical recipe adaptation. What we are trying to do is clear: we are trying to recreate “a taste of the past.” Whether or not we have succeeded we will never know for certain because, unfortunately, there is no one to ask. Still, there are clues. As is often said, ‘the past is a different country.’ If your adapted seventeenth-century dish tastes just like a dish made today, you are probably not succeeding at your task. The dish should taste “foreign.” By “foreign” I don’t mean bizarre. Very few seventeenth-century dishes taste bizarre to a sophisticated modern palate—perhaps few dishes of any time do. To get in the proper spirit, strive to embrace the strangeness of the seventeenth-century repertory, as you would any foreign cuisine. If you do, once you have tried a few recipes, you will key in to the tastes of the day, which will give you a sense of when you are on the right track.

I’m interested in food, and I’m curious to know what it felt like to live three hundred years ago, including what dinner tasted like, so I don’t doubt that recipe adaptation is worth doing. Of course, we must grant that the seventeenth-century recipes we adapt were familiar to only a small cohort of privileged English people, and that some of these recipes, like Ann Smith’s Dutch pie, were probably obscure in their time and so may not reflect the cooking of even this small group. Nonetheless, our recreated dishes do give us at least a taste of that remote time, and they also reveal to us that that time still lingers. Seventeenth-century European visitors to England were struck by the enormous English fondness for meat and sugar. Tourists in America today come away with a similar impression of us.

Finally, you will hear some people opine that historical dishes cannot be recreated because ‘everything was so different then.’ This is silly. By that logic, you also can’t recreate your late Aunt Josie’s potato salad from a recipe card that she wrote thirty years ago. You don’t know the brands of mayonnaise, sweet pickles, sour pickles, mustard, and “seasoned salt” that she bought at her local Piggly Wiggly. You also don’t know what kind of potatoes she used, whether she boiled them whole or peeled and cut up, and whether she served the salad right after she made it or let it sit in the refrigerator for a few days. Indeed, the potato salad that you make following her recipe is not exactly the same as hers. Nonetheless, you have no doubt that it is Aunt Josie’s, even if it lacks her particular touch.

- In theory, a recipe calling for “a peck of flour” should unambiguously mean the old English peck weight of the flour, or 14 pounds, since there was no “peck” liquid measure. However, this seems not to have been the case. In The Compleat Cook (1656), the recipe for Oxfordshire Cake calls for “a peck of flour by weight,” which must mean that “a peck of flour” was sometimes reckoned by the liquid quart, that is, 2 gallons, 8 quarts, or 32 half-pint cups. ↩

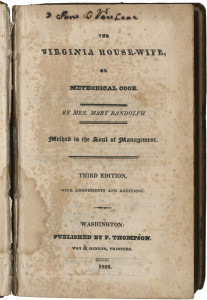

![Mary Randolph[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Mary-Randolph1.jpg)

![grea001[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/grea0011-214x300.gif)