By Stephen Schmidt

Bread, adapted from Mary Randolph’s 1824 recipe

For the first two hundred years or so of European settlement, most Americans lived on isolated farms or in small villages, far from the nearest bakery. Thus, most substantial American homes were built with brick bake ovens, first and foremost for the purpose of baking bread, which most women did once or twice a week, typically on Wednesdays and/or Saturdays. A practice that originated in necessity persisted as a cultural habit to the end of the nineteenth century. By this time, forty percent of the American population lived in cities and towns, and yet nine out of ten American women (by many estimates) still chose to bake their bread at home, now in the convenient ovens of their enclosed iron stoves. There were probably still some women who clung to home bread baking out of fear that bakery white bread was adulterated with chalk, plaster, and other inedible materials, as Sylvester Graham had famously charged—and bakery bread did cost more, if only the materials were considered, than homemade. But reading between the lines of the nineteenth-century bread recipes, many of which go on for pages and frame home-baked bread as a sort of holy manna, I sense that home bread-baking became, over time, a typical nineteenth-century domestic value: something that a good Christian mother did for the health and comfort of her family. In Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book (1845), Catharine Beecher speaks of “sweet, well-raised, home-made yeast bread” as a “luxury” and a “comfort” enjoyed by only a lucky few, who “know that there is no food upon earth, which is so good, or the loss of which is so much regretted.” In The Boston Cook Book (1884), Mrs. Lincoln proclaims that “nothing . . . more affects the health and happiness of the family than the quality of its daily bread,” the home-baking of which “should be regarded as one of the highest accomplishments” of the housewife. With their hyperbole and their Biblical echoes, these recipes seem not to be just about the bread.

Prior to the 1870s, when Fleischmann’s yeast cakes became available, the yeast needed for this project typically originated as a semiliquid byproduct of brewing or distilling—in the case of brewing, either the foam that rose to the top of the barrel during fermentation or the residue left in the emptied barrel, which Americans referred to as “emptins.” To judge from the number of cookbook references, brewer’s yeast was the more common leaven, and “emptins” possibly the more common form, for the word is used to denote a variety of leaveners. However, distillers’ yeast was regarded as stronger and faster-acting.1 Antebellum cookbook authors do not express any preference for one yeast or the other with respect to the taste of the baked bread.

Top Yeast on Fermenting Beer

Charles Louis Fleischmann (1834-1897)

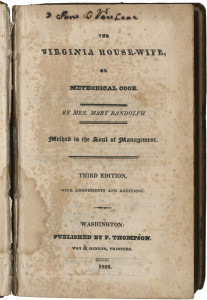

Women who lived close to a brewery or distillery could simply pick up yeast whenever they wanted it and use it straight, and this was the ideal way, according to the cookbook authors. In The Virginia House-Wife (1824), Mary Randolph advises, “Persons who live in towns, and can procure brewer’s yeast, will save trouble by using it,” sentiments echoed by Eliza Leslie, in Directions for Cookery (1837), who writes, “Strong fresh yeast from the brewery should always be used in preference to any other.” But many women could only procure brewery or distillery yeast periodically, and so they had to grow the yeast they bought into a larger batch and preserve this batch for some weeks or months. And thus we find many recipes for yeast in antebellum American cookbooks, both print and manuscript.

Maria Parloa (1843-1909)

Eight years ago I tried the recipe titled simply “Yeast” that is outlined in Maria Parloa’s New Cook Book and Marketing Guide (1881), after I had read about it in Sandra Oliver’s Saltwater Foodways, a fascinating study of nineteenth-century New England cooking on land and sea. The recipe calls for boiling two tablespoons of dried hops in two quarts of water, straining the infusion over six large finely grated raw potatoes, and bringing this mixture up to a boil. This is removed from heat, a half cup of sugar and a quarter cup of salt are added, and, when blood warm, also a cup of yeast—or, interestingly, “one cake of compressed yeast,” which suggests that many women of the 1880s found yeast cakes as hard to come by as their foremothers had found yeast from a brewery or distillery. The mixture is allowed to rise for five or six hours in a warm place. Then it is turned into a “stone jug,” corked tightly, and “set in a cool place.” I made a half recipe, using three 8-ounce baking potatoes and 1 teaspoon of granulated dry yeast (which is more or less equivalent to one half cake of compressed yeast). I got a total of three quarts, which I kept in a glass Mason jar in the refrigerator. I was able to make bread with this yeast from mid-April to mid-August—by which point I had used up the entire batch—using 1/3 cup of yeast to 14 ounces of flour, that is, flour sufficient for one standard loaf. Granted, by the time of my last batch of bread, the dough took some eighteen hours to rise to double in the bowl and another two hours in the pan. But this is only a little more time than Mary Randolph anticipates that it will take her bread to rise, including an initial setting of a sponge (which I did not do in making my own loaves).

Hop Plants

Maria Parloa’s yeast astonished me. I would never have guessed that a mere teaspoon of dry yeast could be stretched to raise twelve loaves, or some sixteen pounds, of bread. I was even more surprised that the yeast remained alive and active, if sluggish, over a period of four months. The secret to its longevity may have been the hops, an ingredient in most antebellum yeast recipes. (I got my hops from “hop tea,” which is sold at natural foods stores, in individual teabags.) David Yudkin, owner of Hotlips Soda, in Portland, Oregon, explained to me that hops is a mild antibacterial. In beer, it allows for yeast fermentation but suppresses other organisms, thus acting as a preservative, and it presumably does the same in homemade yeast. In fact, my batch of yeast had begun to smell sour as early as May, which suggests that organisms other than yeast were growing in it. However, these organisms did not kill the ferment and, just as importantly, their sourness was not imparted to the bread, a critical issue for antebellum bread bakers—more about this in a moment.

Hop Flowers, or Hops

I more or less forgot about my 2009 home yeast experiment until a couple of months ago, when I received an intriguing bread recipe from John Buchtel, Director of the Booth Family Center for Special Collections of the Lauinger Library, at Georgetown University. This bread was baked by one Brother Gavan, the head of the Georgetown campus bakery, around the time of the Civil War, and it was a large batch indeed, made with “a barrel of flour.” Assuming that the flour weighed around 200 pounds (196 pounds is the understood weight of a barrel today) and the dough was made up with 60% as much water by weight as flour (which is Mary Randolph’s hydration; Brother Gavan’s recipe is unclear on this point), the recipe yielded around 300 pounds of baked bread. The yeast used in this recipe captured my attention. It is made in two stages. First, “a quart of stock yeast,” presumably from a brewery or distillery, is fermented for 24 hours in a slurry of hop “juice” (made by boiling one ounce of dried hops in a gallon of water for half an hour), four ounces of wheat flour, and one ounce of malt flour (ground dried sprouted barley). This, strained, makes what the recipe refers to as “the yeast.” In the second stage, this yeast (measuring about one gallon) is combined with a “bucket of potatoes,” boiled and mashed (“skins and all”), four pounds of flour, and eight gallons of water, and this mush is allowed to “ripen” in a “tub of double capacity for . . . 12 to 13 hours.” This, strained, is used to make a sponge, and the sponge, presumably with additional water, is kneaded up into the dough.

I assumed at first that only large-scale bakeries would make use of a two-stage yeast brewing process, whose point, I inferred, was to provide the yeast with two separate feedings, thereby growing a small amount of stock yeast into sufficient leavening for an enormous quantity of bread. But I had a nagging suspicion that I had seen similar recipes in home cookbooks too, and indeed I had. Here is one from the “Jane E. Hassler cookbook, June 1857,” a manuscript cookbook in the possession of the University of Iowa:

Fountain Rising

Boil a large handful of hops, in about 3 qts of water, several hours, put it boiling hot on about 1 qt of Rye flour. Taking care to wet every part, when cool enough, add some leaven to make it rise, 2 spoonful of salt, Ginger, and sugar each, when light, beat it down, and let it rise again. Cover it well from the air, and keep it in a cool place.

When you boil potatoes pour the water on some flour, and mash a few potatoes with it, when cool stir a large handful of the rising above mentioned, and then set your bread to rise with it afterwards.

This recipe calls for considerably more yeast food (rye flour) in the first stage than Brother Gavan’s recipe does, and it is presumably this food that keeps the yeast fed during storage, just as grated potatoes do in Maria Parloa’s recipe. Although the recipe does not say so, I assume that the second stage of Fountain Rising includes a fermentation period, during which the yeast gains strength by feeding on the potatoes. While not facing the Herculean task of leavening 300 pounds of bread, as Brother Gavan’s yeast must, Fountain Rising will have become fatigued if it has been kept for some weeks or months. The second feeding will revivify it, so that, with luck, it will raise the dough in something less than eighteen hours.

Many antebellum yeast recipes look much like Maria Parloa’s (albeit typically with mashed cooked potatoes rather than grated raw), a few like Fountain Rising. And there are many others too, some sustained with whole wheat flour or pumpkin, some without hops (which Beecher contends can give bread an unpleasant sharpness), and more than a few with ginger, which was perhaps believed to increase the liveliness of yeast because it is “hot.”2 There are also yeast “cakes,” which Mary Randolph, in common period fashion, makes by thickening a yeasted hop slurry with cornmeal to “the consistency of biscuit dough,” rolling and cutting the dough into “little cakes,” and drying them “in the shade, turning them frequently.” There are also recipes for (liquid) yeast that do not call for stock yeast, apparently relying on wild yeasts for leaven. Catharine Beecher outlines such a recipe in her cookbook of 1845, under the title “Milk Rising.” A similar recipe also appears in “American Cookbook, 1824-1855,” a manuscript cookbook at the University of Iowa:

Milk Emptins

Boil one pint of new milk then add one pint of water and stir in flour till about as thick as slapjack & let it stand over night & it is fit for use

I am curious about all of these yeast recipes, and I wish that I had the time and patience—and the yeast expertise—to explore them. But I don’t, so I will assume, on the basis of my yeast experiment eight years ago, that most of these recipes work, perhaps far better and far longer than I would think from reading them on the page. I am tempted also to assume that home-brewed yeasts imparted more or less the same flavor to antebellum bread that supermarket yeast imparts to bread today, for, in fact, the bread I raised with my home-brewed yeast tasted entirely familiar. But, obviously, I cannot make such an assumption because the original leaven in my home-brewed yeast came from the supermarket.

Barrel of Branded Flour

Unfortunately, this is only one of many assumptions that cannot be made in attempting to replicate the standard antebellum American white loaf. Indeed, it is probably an error to even speak of such a thing. Although there were flour brands as early as 1800, they were not graded by standard protocols, as all commercial flours are today, and people bought these flours on the basis of diverse criteria. (There is much advice on this score in the cookbooks.) And many women baked bread using local flour, perhaps ground from wheat grown on their family’s fields. So the flours that went into antebellum loaves must have varied considerably with respect to protein and starch content, moisture, grind size, and degree of bolting, resulting in rather different antebellum loaves. That said, based on my experience with adapting antebellum recipes generally, I suspect that antebellum flours, as a rule, had considerably less protein and absorptive capacity than today’s “bread flours” and less even than today’s higher-protein all-purpose flours. If this was indeed the case, relatively low-protein all-purpose flours (about 10.5%), such as Gold Medal and Pillsbury brands, should be as close to the mark as it is possible to come.

Additional difficulties in arriving at a standard antebellum white loaf are posed by the period recipes. Perhaps because flours varied so greatly, most antebellum recipes are maddeningly sketchy with regard to hydration, the crucial determinant of texture. Eliza Leslie’s directions are typical. She says only to add “as much soft water as is necessary” to mix the sponge and the remaining flour called for in her recipe into dough, which could imply a hydration anywhere between 50% and 65%. Making matters still more complicated, antebellum recipes call for wildly divergent proofing times, the critical factor for flavor. After kneading her sponge into dough, Leslie says to set the dough “in a warm place to undergo a further fermentation; for which, if all has been done rightly, about twenty minutes or half an hour will be sufficient.” A twenty- to thirty-minute rise does not strike me as even remotely sufficient, but, in fact, cookbook author Mary Cornelius, in the 1859 edition of The Young Housekeeper’s Friend, does not proof her dough at all. (Granted, Cornelius allows her sponge to rise overnight, which would have helped.) On the other hand, there is Mary Randolph. She allots around five to seven hours for setting the sponge (depending on the season) and she proofs the dough overnight.

Antebellum bread recipes stress two points in particular. First, the dough must be thoroughly kneaded (for as long as thirty minutes, says Leslie) in order that the bread be “white and light,” says Beecher. Second, as Mary Cornelius puts it, “Care is necessary that bread does not rise too much, and thus become sour.” Eliza Leslie says the same, and so does Catharine Beecher, adding that over-risen bread can “lose its sweetness” even “before it begins to turn sour.” Sourness being so abhorrent, all antebellum cookbook authors give directions for correcting soured doughs by kneading in a solution of water and pearl ash or saleratus, alkaline compounds more commonly used as baking sodas. Unfortunately, soda is damaging to the texture of bread, turning it crumbly and dry, like a baking powder biscuit, as Catharine Beecher acknowledges, writing, “Bread is never as good which has turned sour, and been sweetened with saleratus, as if it had risen only just enough.”3 Some culinary historians have written that antebellum American bread was a species of sourdough. These people are mistaken. The word repeatedly used in antebellum recipes to describe the desired flavor in bread is sweet.

Mary Randolph (1762-1828)

Those determined to make an antebellum loaf—if not a standard loaf and possibly not even a typical one—can find no better guide than Mary Randolph. Randolph provides proofing times for both the sponge and the dough, she specifies the hydration, and—miracle of miracles—she correlates the volume measure and the weight of wheat flour. And her correlation (one quart of flour weighs one and one quarter pounds) is precisely accurate for today’s all-purpose flour, which tempts one to think (perhaps wishfully) that her recipe, adapted with all-purpose flour, yields bread similar to the bread she baked.

To Make Bread

Mary Randolph, The Virginia House-Wife (1824)

When you find the barrel of flour a good one, empty it into a chest or box made for the purpose, with a lid that will shut close; it keeps much better in this manner than when packed in a barrel, and even improves by lying lightly; sift the quantity you intend to make up, put into a bowl three quarters of a pint of cold water to each quart of flour, with a large spoonful of yeast, and a little salt, to every quart; stir into it just as much of the flour as will make a thin batter, put half the remaining flour in the bottom of a tin kettle, pour the batter on it, and cover it with the other half; stop it close, and set it where it can have a moderate degree of warmth. When it has risen well, turn it into a bowl, work in the dry flour and knead it some minutes, return it into the kettle, stop it, and give it moderate heat. In the morning, work it a little, make it into rolls, and bake it. In the winter, make the bread up at three o’clock, and it will be ready to work before bed time. In summer, make it up at five o’clock. A quart of flour should weigh just one pound and a quarter.

Loaves Cast on Oven Floor

Randolph makes up her bread as “rolls,” by which she does not mean rolls as we now think of them but, probably, small eight- to ten- ounce round loaves, hand-shaped and baked free-standing, similar perhaps to the fine white loaves that the seventeenth-century English called manchet, or so Karen Hess speculates in her annotations to Randolph’s recipe in the 1984 South Carolina Press edition of Randolph’s cookbook. Historically, breads baked freestanding were typically cast from a peel directly onto the oven floor, which has led some authorities to surmise that the pan-baking of American bread came in with the introduction of enclosed stoves, whose slatted oven shelves made such a maneuver impossible. However, in The American Frugal Housewife (1833), Lydia Maria Child bakes her bread in pans—in a brick oven. So it seems that the stove oven did not usher in pan baking but sealed the transition to it, which had already begun by the time Randolph wrote.

Like the classic French baguette, Randolph’s bread is made with four simple ingredients: flour, water, yeast, and salt. This was typical—possibly even ubiquitous—in this country for all loaves simply called “bread” until around 1850, when water came to be replaced, at least in part, with milk. After the Civil War, small amounts of shortening and sugar were introduced, and today’s standard American “white bread” was born. Bread aficionados might enjoy baking my adapted recipe for Randolph’s bread side-by-side with a modern American white bread that includes milk but has a similar hydration, perhaps the classic Joy of Cooking White bread (which appears in all editions) or the richer Pullman Loaf from the excellent Hot Bread Kitchen Cookbook.4 While Randolph’s bread is a bit different from its modern counterparts—firmer and more cohesive, slightly less white in color—it has the same thin crust, the same small, tight crumb, and a similar flavor: unmistakably an American loaf.

- I gather from what I’ve read—and I am hardly an expert—that today’s brewery and distillery yeasts are different strains of the same organism. ↩

- Some contemporary research suggests that certain spices promote the growth of yeast, while others inhibit it. ↩

- The yeast, too, was supposed to be sweet, and, to keep it sweet, Leslie recommends recourse to pearl ash: “It is best to make yeast very frequently; as, with every precaution, it will scarcely keep good a week, even in cold weather. If you are apprehensive of its becoming sour, put into each bottle a lump of pearl-ash the size of a hazel-nut.” If yeast did turn sour, Beecher did not think alkali correction would help: “Sour yeast cannot be made good with saleratus.” As I have said, my sour-smelling home-brewed yeast produced perfectly sweet bread. ↩

- Correcting for the milk used in the modern loaves, which contains 15% materials other than water, their hydrations are approximately 68%, comparable to the hydration of Randolph’s loaf and promoting a similar texture. ↩

![Boston, Massachusetts 1860 City Directory Page 152, which lists Flint, Waldo, pres. Eagle Bank, 16 Kilby, h. [house] 6 West](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2016-4-23-152-181x300.jpg)

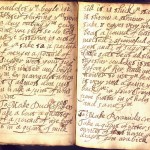

foods comprised a whole ham and four chickens. Another supper featured the same cold dishes plus lobster salad, and another tempted guests with four cold chickens with “celery dressed” and four cold geese (a rather strange idea, at least to most people today). The cold foods were paired with an equally bountiful array of hot items. At most suppers, Mrs. Flint served three or four hot ducks plus four hot grouse or partridges, though at one supper she offered instead a turkey (with deep-fried mashed potato balls) and six roasted pigeons. I suspect that the turkey was boiled, and that the grouse and partridges served at the other suppers were boiled too. The many hot birds on these menus would not all have fit in a period stove oven, and boiling was then a common way to cook poultry, at least of certain types.

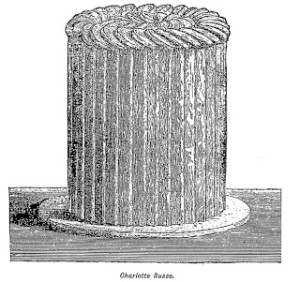

foods comprised a whole ham and four chickens. Another supper featured the same cold dishes plus lobster salad, and another tempted guests with four cold chickens with “celery dressed” and four cold geese (a rather strange idea, at least to most people today). The cold foods were paired with an equally bountiful array of hot items. At most suppers, Mrs. Flint served three or four hot ducks plus four hot grouse or partridges, though at one supper she offered instead a turkey (with deep-fried mashed potato balls) and six roasted pigeons. I suspect that the turkey was boiled, and that the grouse and partridges served at the other suppers were boiled too. The many hot birds on these menus would not all have fit in a period stove oven, and boiling was then a common way to cook poultry, at least of certain types.  Seemingly patterned after the fancy new dinner service called à la russe, the final courses of the suppers were incredibly lavish. On February 2, 1860, Mr. Flint’s twelve guests were confronted with one quart of charlotte russe, one quart of frozen pudding, three pints of Roman punch, three pints of vanilla ice cream, and two one-quart molds of calves’ foot jelly

Seemingly patterned after the fancy new dinner service called à la russe, the final courses of the suppers were incredibly lavish. On February 2, 1860, Mr. Flint’s twelve guests were confronted with one quart of charlotte russe, one quart of frozen pudding, three pints of Roman punch, three pints of vanilla ice cream, and two one-quart molds of calves’ foot jelly ![Mary Randolph[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Mary-Randolph1.jpg)

![grea001[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/grea0011-214x300.gif)