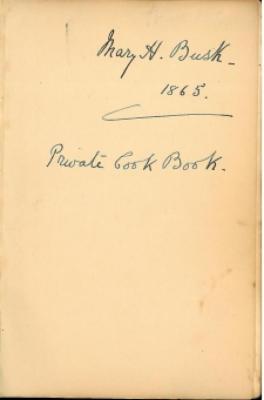

Mary H. Busk Private Cookbook, with Additions by Her Daughter, 1865-1928

View Catalog Record

[Library Title: Manuscript Cook Book]

[Library Title: Manuscript Cook Book]

Manuscript Cookbooks Survey Database ID#

1283Place of Origin

United States ➔ New York ➔ New YorkDate of Composition

1865-1928Description

This cookbook is compiled in an octavo notebook bound in leather and stamped with the initials of the primary author, Mary Hamilton Busk, on the upper cover. It is signed by Busk and dated 1865 on the front endpaper.

Busk (1841-1916) was born Mary Hamilton Laird in Birkenhead, England, to a family of shipbuilders. She married Joseph Richard Busk in 1863, two years before beginning this cookbook. The Busks lived in New York City—one of the loosely inserted recipes was written on stationery engraved with the address 830 Park Avenue—and summered in Newport, Rhode Island, a favorite summer retreat of the wealthy. According to her obituary in the New York Times, Busk was a member of Trinity Church in Newport, and was survived at her death by her daughter, Margaret, and three sons.

The book comprises 128 pages of written recipes as well as 47 pages of recipes clipped from various printed sources, some pasted into the book and some loosely inserted. While mostly culinary, some of the recipes pertain to cleaning and maintaining the kitchen and household. Most of the recipes include the places where they were collected, and some are also dated. Among the places referenced are New York City (fondue, 1868), Staten Island, New York (stuffed eggplant); New London, Connecticut (clam fritters and devilled lobster); Ascot Place, England (eggs dressed as plover's eggs, 1874); Bradford Street (a summery-sounding “rhubarb mould,” 1883); Indian Spring; Bar Harbor, Maine; Aldenham Lodge, Hertfordshire, England; and Chamonix, France. There are also a number of recipes from Birkenhead, England, Mary Busk’s birthplace.

Mary Busk’s cookbook traces the culinary tastes an upper-middleclass family between the Civil War and World War I. This was the so-called Gilded Age, when American cooking became pervaded by French influences, and expensive, showy, sometimes pretentious dishes were in vogue. The multi-course dinners served à la russe that were fashionable at the time often began with clear soup, so it is not surprising that Busk's first entry is "Patties for soup." Patties were little patty shells, ideally of puff paste, filled with sauced shellfish or meat.

Any cold meat pounded and flavored with mace if white meat; and allspice if brown, and a little pepper and lemon peel. The crust must be thin and very good paste which before putting in the oven you egg over and sprinkle with vermicelli. Serve these on a napkin with clear soup.

More down to earth is Busk’s "Gumbo soup," which she collected in West Point, in 1866:

Cut a slice of ham in small pieces, a young chicken or turkey cut in joints and fried a nice brown with an onion and a spoonful or two of lard. These to be put into a covered pot with half a gallon of broth and stewed an hour or two very gently. Just before serving stir in gently half a table spoonful of "Sassafras filé" or powder and let it boil up well. In using ochra instead of file it must be put into the soup much earlier as it must be cooked very thoroughly. All must be quite soft and some boiled to rags. Oysters and tomatoes may be added with advantage.

Terrapins—turtles of various kinds—were basis for some of the era’s most prestigious soups and stews. Busk cooks the creatures thus: "Let them simmer in a vessel of water until you think them perfectly clean, then put them into a pot of boiling water and let them boil until you can loosen the outside skin above the feet - Select the meat from the shells, but do not disturb the gall." She dated the recipe 1876, and wrote, "This is the Baltimore way of cooking terrapins."

The Gilded Age delighted in colored foods—indeed in entire meals colored white, green, brown, or whatever. The following "Birds Nest Salad" is a variation on that theme:

Put a little green coloring into cream cheese, giving it a delicate color like birds eggs: roll it into balls size of birds eggs. Arrange some crisp lettuce leaves on a flat dish, group them to look like nests, moisten with pinch dressing and place some of the cheese balls in each nest of leaves. The cheese balls may be varied by flecking them with black or red pepper.

Busk cut out 17 pages of printed recipes from "The Cook" and pasted them into her cookbook. Busk annotates one of these recipes, Cheese Toasts, as "good"—and after reading the recipe, one can see why:

Put half an ounce of butter in a frying pan; when hot, add gradually four ounces of mild American cheese. Whisk it thoroughly until melted. Beat together half a pint of cream and two eggs; whisk it into the cheese, add a little salt, pour over toast, and serve.

Mary Busk's final recipe is "Sardine Savoury," which she recorded in Indian Spring in 1916, the year she died. There is a blank page after this recipe, followed by 23 pages of additional recipes written by her daughter Margaret. Margaret's first entries are two typed recipes for making and serving "good" coffee. On the page opposite these recipes, Margaret wrote a third coffee recipe, which instructs, "Double boiler for milk, [ ] not to boil. If coffee has to stand put it in a double boiler: to keep hot. [ ] put through Percolator once. Grind fine and evenly." Margaret’s recipes mimic her mother’s in that many include the place where they were collected and are often dated, from 1917 to 1928. Also like her mother, Margaret collected recipes in France, including two recipes for Bouillon de Légumes, one from Marie-Pau, in 1927, and one from Villa de Nantes/Chamonix, in 1928.